Mobilization and Mutiny

Sidney Rodger Collection, Beamsville, Ontario

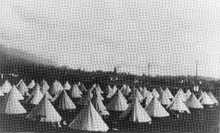

French-Canadian conscripts at a “Hands Off Russia” meeting, Victoria, 13 December 1918. This dialogue between Quebecois soldiers and British Columbia workers contributed to the mutiny of 21 December 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

On 21 December 1918, French-Canadian soldiers mutinied in the streets of Victoria, British Columbia. Conscripts in the 259th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia) (CEFS), these men broke ranks while marching from the Willows Camp to the troopship SS Teesta, about to embark for Vladivostok, Russia. At the corner of Fort and Quadra streets, rifleman Onil Boisvert, a 22-year-old farmer from Drummond, Quebec, defiantly shouted “On y va pas à Siberia!”

Two companies refused to march. The revolt was suppressed as officers fired revolvers and loyal soldiers removed canvas belts to whip the mutinous back into line. The soldiers proceeded at bayonet point to the Outer Wharf, where it took 23 hours to herd the troops aboard the SS Teesta. Rfn. Boisvert and a dozen ringleaders were shackled in the ships’ hold for the three-week voyage to Vladivostok.

What had brought this disturbance about?

Mobilizing the Siberian force

Library and Archives Canada, Imperial Oil Collection, 1972-026, IC-31

"Troops at Petawawa: Canadian Troops Marching Off to Siberia,” original drawing by C.W. Jefferys, 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

On 12 August 1918, Canada's privy council had passed Order-in-Council PC 1983, approving the formation of the CEFS, which consisted of 4,209 men and one woman — nursing matron Grace Elrida Potter. In a diplomatic coup for Canada, 1,500 British troops in the Middlesex and Hampshire regiments were placed under the command of Canadian Major-General James H. Elmsley.

The CEFS was mobilized from every province. It consisted of two infantry battalions in the 16th Canadian Infantry Brigade, as well as machine gun, artillery, and engineering companies and smaller units of bakers, butchers, medics, and other supporting troops. Two hundred Mounties from the Royal North West Mounted Police (RNWMP) deployed to Vladivostok, along with 300 horses.

One third of Canada’s Siberian troops were conscripts, compelled to serve under the Military Service Act 1917. Their mobilization coincided with the Armistice that ended fighting on the Western Front, as well as the Spanish Flu that ravaged civilian and soldier populations across Canada and the globe. As the troops converged on barracks at Victoria, New Westminster, and Coquitlam, British Columbia, dissent encouraged by local labour radicals erupted into mutiny.

Converging on the Willows Camp

Sidney Rodger Collection, Beamsville, Ontario

View from the Canadian Pacific Railway in the Rocky Mountains, October 1918. The Spanish Flu reached Canada’s west coast on these Siberia-bound troop trains.

View more photos like this in the archive

The troops mobilized to the West Coast as Canada experienced the gravest casualties of the First World War — nearly 6,000 troops died on the Western Front in September and October 1918. With voluntary enlistments dried up, the government used the Military Service Act to conscript 1,653 troops into the CEFS.

The 259th Battalion (Canadian Rifles) was commanded by Lieut-Col. Albert "Dolly" Swift, a career soldier who organized his headquarters at Montreal's Peel Street Barracks. The battalion consisted of:

- A Company - Toronto military district

- B Company - Kingston and London military districts

- C Company- Montreal military district

- D Company - Quebec City military district

The 260th Battalion (Canadian Rifles) was commanded by Lieut-Col. F.C. Jamieson and consisted of:

- A Company - Nova Scotia and New Brunswick

- B Company - Manitoba

- C Company - Saskatchewan and Alberta

- D Company - British Columbia

John Skuce, CSEF: Canada's Soldiers in Siberia 1918-1919 (Ottawa: Access to Historical Publications, 1990)

Under canvas at Coquitlam, British Columbia, c. November 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

The CEFS mobilized as the Spanish Flu hit Canada — the world-wide influenza epidemic that took an estimated 60 million lives globally and killed 101 people in Victoria, with more than 2,800 falling ill. Recent research has shown that the Spanish Flu reached Western Canada aboard the Siberia-bound troop trains. Medical records for hospitals in Winnipeg, Calgary and Vancouver show the first reported cases of the illness occuring within hours of the CEFS trains passing through the cities.1

Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection

Canadian soldiers in their bunkroom, Queens Park, New Westminster, BC, c. October 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

In British Columbia, some units were quartered under canvas at Coquitlam, east of Vancouver, while others including members of RNWMP 'B' Squadron trained at the Queen's Park barracks in New Westminster. However, the majority of the CEFS — approximately 3,000 troops — sailed by overnight steamer to Victoria, marching across the city to the Willows Camp in the affluent municipality of Oak Bay.

Armistice and Unrest

The soldiers reached Canada's West Coast in October 1918 — just weeks prior to the Armistice that ended four years of fighting on the Western Front. With the signing of the Armistice, many Canadians opposed the Siberian Expedition. This opposition extended from Borden's Cabinet ministers, to farmer organizations such as the United Farmers of Ontario, to the labour councils of Canada's four largest cities, and to the Siberian troops themselves.

Library and Archives Canada, Dorothy I. Perrin Collection, e010752824

Inspection of the 259th Battalion at the Willows Camp, Victoria, December 1918. As the Daily Times reported, “It may not have been the best time of year for troops to have been quartered in Victoria… The latter part of their stay has been marked by an unusual amount of rain with an attendant sea of mud at the Willows."

View more photos like this in the archive

When combined with a wet British Columbia autumn and the Spanish Flu, it was an explosive situation.

As Borden sailed across the Atlantic to peace talks in Europe, he received an urgent telegram from acting-prime minister Sir Thomas White (the first in a long series of tense correspondence that preceded the troops' departure for Russia):

All our colleagues are of opinion that public opinion here will not sustain us in continuing to send troops, many of whom are draftees under the Military Service Act and Order in Council, now that the war is ended. We are all of opinion that no further troops should be sent and that Canadian forces in Siberia should, as soon as situation will permit, be returned to Canada. Consider matter of serious importance.2

The prime minister ignored his ministers' advice and decided that the mission would proceed, regardless of the Armistice in Europe.

PROFILE

Rifleman Onil Boisvert and the Victoria Mutiny of 21 December 1918

Karel Ménard Collection, Montréal, Québec

Rifleman Onil Boisvert, one of the Quebecois soldiers convicted of mutiny at Victoria, c. autumn 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

Viateur Beaulieu Family Collection, Cacouna, Quebec

“D” Company of the 259th Battalion at the Willows Camp, Victoria, before their departure for Vladivostok, December 1918. This unit was mobilized from the Quebec City military district and emerged as the locus of dissent. Several soldiers were later court-martialed in relation to the Victoria mutiny of 21 December 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

In the summer of 1918, Onil Boisvert was conscripted into the Canadian army under the authority of the Military Service Act, a controversial law that had provoked rioting in Quebec. The farmer from the town of Drummond was attached to “C” company of the 259th Battalion (Canadian Rifles). Mustered to the Peel Street Barracks at Montreal, Boisvert was hospitalized on account of the Spanish Flu, while his unit was placed under quarantine. At the end of October 1918, Boisvert and "C Company" deployed along the Canadian Pacific Railway to British Columbia.

Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection

Major-Gen. C.W. Leckie inspects soldiers of the 259th Battalion at the Willows Camp, Victoria, December 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

Onil Boisvert was quartered at the Willows Camp in Victoria, as a wet British Columbia autumn and the arrival of the Spanish Flu sapped the morale of Siberian troops. They began attending labour protest meetings in large numbers, where speakers from the Socialist Party of Canada and Federated Labor Party issued the demand “Hands Off Russia.”

Sidney Rodger Collection, Beamsville, Ontario

Soldiers from the 259th Battalion on day leave in downtown Victoria, December 1918. Public gatherings had been banned by the city's health committee, in an attempt to curb the influenza epidemic. Once the ban was lifted, soldiers make full use of their leisure time.

View more photos like this in the archive

Sidney Rodger Collection, Beamsville, Ontario

French-Canadian conscripts of the 259th Battalion at a “Hands Off Russia” mass meeting, Columbia Theatre, Victoria, 13 December 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

Despite efforts by the military command to counter the influence of these labour meetings, discontent grew. When Boisvert (like his platoon comrades) was asked to volunteer for service in Siberia, he refused, believing that “as a farmer I was more useful at home.” Boisvert joined 300 other Siberian conscripts in sending an urgent telegram to Ottawa, requesting that they not be sent to Siberia. However, citing commitments made to the British government and “certain well disposed persons in Russia,” the government of Sir Robert Borden ordered their deployment to Vladivostok.3

British Columbia Archives, I-78248 / HP018921

Soldiers marching toward the Victoria's Rithet's Wharf, December 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

Before dawn on the morning of 21 December 1918 — the shortest day of the year — Boisvert and other French-Canadian conscripts in the 259th Battalion were rousted out of their tents and ordered to march from the Willows Camp to Victoria’s outer wharf, a distance of about six kilometres. When they reached downtown Victoria, and took a routine break at the corner of Fort and Quadra Streets, Boisvert and his platoon refused to resume the march. The commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Albert “Dolly” Swift, ordered the conscripts to march. Boisvert refused, as a comrade struck the battalion's Catholic chaplain with his fist. Swift then fired his revolver at Boisvert's feet. Boisvert shouted “On y vas pas à Siberia!”4

To suppress the mutiny, Swift ordered the obedient troops, volunteers from Toronto and Kingston who belonged to “A” and “B” companies of the 259th Battalion, to remove their canvas belts and whip Boisvert and the mutinous back into line. “They did it with a will and we proceeded, they being far more closely guarded than any group of German prisoners I ever saw,” a lieutenant later wrote in a letter to his wife.5 A “guard of honour” (fifty troops with fixed bayonets) was summoned to escort the mutineers toward the ship at the point of the bayonet.

It took 23 hours to herd the 259th Battalion aboard the waiting troopship SS Teesta, where Boisvert was handcuffed along with a dozen ringleaders in the ship’s hold. They were not allowed to shower or change clothes for 38 days, at which time Boisvert was court-martialled and sentenced to two-years hard labour for the crime of “joining in mutiny while on active duty in His Majesty's armed forces.” Early on the morning of 22 December 1918, Onil Boisvert and the 259th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia) sailed from Victoria to Vladivostok.

The Protesilaus

Five days behind the SS Teesta, the Blue Funnel liner SS Protesilaus pulled out of Victoria with an additional 1800 enlisted men and 170 officers. The ship had been hastily retrofitted to accommodate the 2,000 soldiers — half were quartered in bunks while the remainder slept in hammocks strung haphazardly below deck. Conditions aboard the Protesilaus — which later resulted in a Court of Inquiry by the Canadian command — are conveyed in a satirical poem by working-class poet Dawn Fraser, a pharmacist from Saint John, New Brunswick, who voluntary enlisted in the 260th Battalion:

An over-loaded stomach, or may-be it was fear,

My hammock tossing wildly, my head was feeling queer;

The boat was tipping madly, the breakers fairly screamed;

I have no idea what time it was, I fell asleep and dreamed.

That the old Protesilaus dumped us out, along with all her crew,

And we struggled vainly, vainly, in an Ocean made of Stew.6– "Boulion à la SS Protesilaus," Dawn Fraser, from Songs of Siberia and Rhymes of the Road (1919)

British Columbia Archives, I-78247 / HP018920

SS Protesilaus about to leave Victoria, 26 December 1918. At sea, a soldier and a crewmember died in accidents and the ship lost its port propeller after getting stuck in the north Pacific ice.

View more photos like this in the archive

At sea, conditions were grim. The ship was heavily overloaded and battled rough weather all the way to Vladivostok. On 30 December 1918, four days after leaving Victoria, the ship encountered a storm. Private Harold Butler was killed and two other soldiers injured when a large case of ice and meat broke loose from its mountings and crushed them. “It was sickening,” Lieutenant Stuart Tompkins recalled.7

Two days later, a Chinese crew member went overboard during a storm and died. As the ship approached Russia, it encountered bad weather again, losing its port propeller and becoming stuck in the ice fifty kilometres east of Vladivostok. The Protesilaus sent an SOS message by wireless. When word reached Vladivostok, two British cruisers were readied for departure. However, the Protesilaus sent a second wireless with its location and the message: “no assistance required.” As Captain Eric Elkington recalled seven decades later: “We were rescued by a Japanese war ship.”8

The Protesilaus limped towards Vladivostok on the power of a single propeller.

Notes

- 1 Mark Osborne Humphries, “The Horror at Home: The Canadian Military and the ‘Great’ Influenza Pandemic of 1918,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 16, 1 (2005): 235-60.

- 2 White to Borden (via Sir Edward Kemp, overseas minister), 14 November 1918, Library and Archives Canada, Borden Papers, MG 26, ser. H1(a), vol. 103.

- 3 Borden to White, 7 December 1918, Library and Archives Canada, RG 24, ser. C-1-A, vol. 2557, file HQC-2514 (vol. 1).

- 4 Testimony of Major Guy Boyer, Lieutenant T.J. Morin, Captain G.N. Oliver, Lieutenant L.H.G. Van Boren, Sergeant R. Belleau, Captain S.M. Rapin, “Trial of No. 3312133 Rifleman Arthur Roy,” 28 January 1919, “Summary of Evidence for the Trial of No. 3312133, Rfn. Arthur Roy,” 27 December 1918, and “Schedule No. 3312133, Rfn. Arthur Roy” (all in Library and Archives Canada, RG 24, ser. C-1-A, vol. 1992, file H-Q-762-11-10, “Courts Martial in CEF [Siberia]”).

- 5 “What a Muddle,” BC Federationist, 28 February 1919.

- 6 “Boulion a là SS Protesilaus,” in Dawn Fraser, Songs of Siberia and Rhymes of the Road (Glace Bay, NS: Eastern Publishing, c. 1919), 21. See also “No. 254 Court of Inquiry,” 26 March 1919, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), Daily Routine Orders, March 1919, app. 41, p. 26.

- 7 Tompkins to Edna, 30 December 1918, reprinted in Stuart Ramsey Tompkins, A Canadian’s Road to Russia: Letters from the Great War Decade, ed. Doris H. Pieroth (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1989), 364. See also Ardagh Diary entry, 3 January 1919, LAC, Ardagh Fonds, MG 30, E-150, file 1/6; War Diary of 16th Infantry Brigade Headquarters CEF(S), 30 December 1918.

- 8 Eric Henry William Elkington interview, 24 January 1986, University of Victoria Special Collections, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 170.

Go to

Mobilisation et Mutinerie

Collection Sidney Rodger, Beamsville, Ontario

Conscrits canadiens-français assistant une réunion « Hands Off Russia », Victoria, 13 décembre 1918. Le dialogue entre soldats québécois et travailleurs de la Colombie-Britannique contribua à la mutinerie du 21 décembre 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Le 21 décembre 1918, des soldats canadiens-français mutinèrent dans les rues de Victoria, Colombie-Britannique. Conscrits du 259e Bataillon de la Force Expéditionnaire canadienne (en Sibérie) (FECS), ces hommes rompirent de leurs rangs pendant leur marche du Camp Willows pour le navire SS Teesta, qui préparait son départ pour Vladivostok, en Russie. Au coin de la rue Fort et Quadra, Onil Boisvert, un agriculteur de 22 ans originaire de Drummond, au Québec, cria « On y va pas en Sibérie! »

Deux compagnies refusèrent l'ordre de marcher. La révolte fut réprimée lorsque des officiers tirèrent leurs revolvers et des soldats fidèles enlevèrent leurs ceintures pour fouetter les insubordonnés. Les soldats procédèrent à pointe de baïonnette jusqu'au quai, où il prendra 23 heures pour les faire rentrer dans le SS Teesta. Rfn. Boisvert et une douzaine de leaders furent enchaînés dans la cale du navire pour le long du voyage de trois semaines à Vladivostok.

Qu'avait-il mené à cette perturbation?

Mobiliser les forces sibériennes

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, Collection « Imperial Oil », 1972-026, IC-31

« Troops at Petawawa: Canadian Troops Marching Off to Siberia, » dessin original de C.W. Jeffreys, 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Le 12 août 1918, le Conseil Privé du Canada adopta le Décret en Conseil PC 1983, autorisant la création de la FECS, qui se composait de 4209 hommes et une femme - l'infirmière Grace Elrida Potter. Le Canada obtenu une victoire diplomatique lorsque 1500 soldats britanniques des régiments de Middlesex et Hampshire furent placés sous le commandement du Major-Général canadien James H. Elmsley.

La FECS fut mobilisée de chaque province. Elle se composait de deux bataillons d'infanterie de la 16e Brigade d'Infanterie canadienne, ainsi que de mitrailleurs, l'artillerie et les sociétés d'ingénierie et de petites unités de boulangers, bouchers, des médecins, et d'autres troupes de soutien. Deux cents gendarmes de la Royale Gendarmerie à Cheval du Nord-Ouest (RGCN-O) avec 300 chevaux furent déployés à Vladivostok.

Un tiers des troupes canadiennes en Sibérie furent conscrits, engagées sous l'Acte de Service Militaire de 1917. Leur mobilisation coïncida avec l'armistice qui mit fin aux combats sur le Front de l'Ouest, ainsi qu'avec la grippe espagnole, une pandémie mondiale qui frappa les populations civiles et militaires et n'épargna pas le Canada. Comme les troupes arrivèrent aux baraquements de Victoria, New Westminster et Coquitlam, Colombie-Britannique, l'insubordination militaire encouragée par de radicaux travailleurs dégénéra en émeute.

L'arrivé au Camp Willows

Collection Sidney Rodger, Beamsville, Ontario

Vue des Rocheuses du Chemin de Fer Canadien Pacifique Octobre 1918. La grippe espagnole atteignit la côte ouest canadienne grâce aux trains transportant des troupes de la FECS.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Ces troupes furent mobilisées pendant que le Canada connut ces plus grandes pertes de la Première Guerre Mondiale — près de 6000 soldats morts sur le Front de l'Ouest en septembre et octobre 1918. Le gouvernement employa l'Acte de Service Militaire et conscrit 1653 troupes destinées pour la FECS à la suite d'une pénurie de volontaires.

Le 259e Bataillon (Canadian Rifles) fut commandée par le Lieutenant-Colonel Albert "Dolly" Swift, un soldat professionnel qui organisa son quartier général aux baraques de la rue Peel à Montréal. Le bataillon se composait de:

- Compagnie A - district militaire de Toronto

- Compagnie B - districts militaires de Kingston et London

- Compagnie C - district militaire de Montréal

- Compagnie D - district militaire de la ville de Québec

Le 260e Bataillon (Canadian Rifles) fut commandée par le Leutenant-Colonel et se composait de:

- Compagnie A - Nouvelle-Écosse et Nouveau-Brunswick

- Compagnie B - Manitoba

- Compagnie C - Saskatchewan et Alberta

- Compagnie D – Colombie-Britannique

John Skuce, CSEF: Canada's Soldiers in Siberia 1918-1919 (Ottawa: Access to Historical Publications, 1990)

Campement militaire à Coquitlam, Colombie-Britannique, c. novembre 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Les FECS furent mobilisées lorsque la grippe espagnole frappa le Canada - l'épidémie mondiale d'influenza qui tua environs 60 millions de gens, dont 101 à Victoria ainsi que 2800 malades. De récentes études démontrent que la grippe espagnole atteignit l'ouest canadien grâce aux trains transportant les troupes de la FECS. Les dossiers médicaux des hôpitaux de Winnipeg, Calgary et Vancouver démontrent que les premiers cas signalés de la maladie surviennent dans les heures mêmes qu'ils traversaient ces villes.1

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des Archives George-Metcalf

Soldats canadiens dans leurs dortoir, Queens Park, New Westminster, CB, c. octobre 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

En Colombie-Britannique, certaines unités campèrent à Coquitlam, à l'est de Vancouver, tandis que d'autres y compris les membres de l''escadron B de la RGCN-O furent entrainées aux baraquements de Queen's Park, à New Westminster. Toutefois, la majorité du FECS — d'environ 3000 soldats — naviguèrent jusqu'à Victoria et marchèrent au Camp Willows dans la municipalité riche d'Oak Bay.

Armistice et désordres

Les soldats atteignirent la côte ouest canadienne en octobre 1918 - à peine quelques semaines avant l'armistice qui acheva quatre ans de combats sur le Front de l'Ouest. À la suite de l'armistice, de nombreux Canadiens s'opposèrent à l'expédition en Sibérie. L'opposition fut composé de ministres du Cabinet de Borden, d'organisations de producteurs tels que les « United Farmers of Ontario », de conseils du travail des quatre plus grandes villes canadiennes, et même de troupes en Sibérie.

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, Collection Dorothy I. Perrin, e010752824

Inspection du 259e Bataillon au Camp Willows à Victoria, décembre 1918. Le « Daily Times » écrivit que «Ce ne fut pas le meilleur moment de l'année pour cantonné des troupes à Victoria ... La dernière partie de leur séjour fut caractérisé par une pluie inhabituel, et par conséquent par une mer de boue au Camp Willows ».

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

L'automne humide, la grippe espagnole, et l'opposition général contre l'expédition sibérienne créèrent une situation explosive.

Lorsque Borden traversa l'Atlantique pour se rendre aux pourparlers de paix européennes, il reçut un télégramme urgent de Sir Thomas White (le premier message d\une longue série de correspondance qui précéda le départ des troupes canadiennes pour la Russie):

« Tous nos collègues sont de l'avis que l'opinion publique ne nous soutiendra pas dans notre but d'envoyer des troupes, dont beaucoup furent conscrits en vertu de l'Acte de Service Militaire et du Décret en Conseil, maintenant que la guerre est terminée. Nous sommes tous de l'avis qu'aucune autre troupes doivent être envoyées et que les forces canadiennes en Sibérie devraient, dès que la situation le permet, repartir pour le Canada. Considère que cette question est d'une grave importance ».2

Le Premier Ministre ignora les conseils de ses ministres et décida que la mission devait procéder, en dépit de l'armistice en Europe.

PROFIL

Le carabinier Onil Boisvert et la mutinerie du 21 décembre 1918 à Victoria

Collection Karel Ménard, Montréal, Québec

Carabinier Onil Boisvert, l'un des soldats québécois reconnu coupable de mutinerie à Victoria, c. l'automne 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Collection de la famille Viateur Beaulieu, Cacouna, au Québec

Compagnie D du 259ème Bataillon au Camp Willows, à Victoria, avant leur départ pour Vladivostok, décembre 1918. Cette unité fut mobilisé à partir du district militaire de Québec et émergea comme centre de dissidence. Plusieurs des mutins du 21 décembre 1918 passèrent conséquemment en cour martiale.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Onil Boisvert fut conscrit dans l'Armée canadienne sous l'Acte de Service Militaire, une loi controversée qui avait provoqué des émeutes au Québec. Ce fermier de Drummond était attaché à la compagnie C du 259e Bataillon (Canadian Rifles). Rassemblés aux baraquements de la rue Peel à Montréal, Boisvert fut hospitalisé à cause de la grippe espagnole et son unité fut placé en quarantaine. À la fin octobre 1918, Boisvert et la Compagnie C furent déployées en Colombie-Britannique par le Chemin de Fer Canadien Pacifique.

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des Archives George-Metcalf

Major-Général C.W. Leckie inspectant des soldats du 259e Bataillon au Camp Willows, à Victoria, décembre 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Onil Boisvert fut cantonné au Camp Willows à Victoria, pendant que l'automne humide et l'arrivée de la grippe espagnole sapèrent le moral des troupes sibériennes. Plusieurs assistèrent aux manifestations de travailleurs, où les orateurs du Parti Socialiste du Canada et « Federated Labour Party » réclamèrent « Hands Off Russia ».

Collection Sidney Rodger, Beamsville, Ontario

Soldats du 259e Bataillon en congé au centre-ville de Victoria, décembre 1918. Les rassemblements publics furent interdits par le comité de santé de la ville dans une tentative d'enrayer l'épidémie de grippe. Lorsque l'interdiction fut levée, les soldats profitèrent de leurs temps de loisirs.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Collection Sidney Rodger, Beamsville, Ontario

Conscrits canadiens-français du 259e Bataillon lors d'une réunion « Hands Off Russia », au Théâtre Columbia, Victoria, 13 décembre 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Malgré les meilleurs efforts du commandement militaire pour contrer l'influence de ces réunions, le mécontentement des troupes grandit. Lorsque Boisvert et ses camarades de section furent invités à se porter volontaires pour le service en Sibérie, il refusèrent, insistant qu'« en tant que fermier, j'étais plus utile à la maison ». Boisvert rejoignit 300 autres conscrits pour la Sibérie qui demandèrent l'envoi d'un telegram urgent à Ottawa, exigeant qu'ils ne soient pas envoyés en Sibérie. Cependant, citant des obligations envers le gouvernement britannique et « certaines personnes bien disposées en Russie », le gouvernement de Sir Robert Borden ordonna leurs déploiement à Vladivostok.3

Archives de la Colombie-Britannique, I-78248 / HP018921

Soldats marchant vers le quai Rithet à Victoria, décembre 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Le Matin du 21 Décembre 1918 - le jour le plus court de l'année — avant l'aube, Boisvert et d'autres conscrits canadiens-français du 259e Bataillon furent réveillés, forcés de leurs tentes et ordonnés de marcher du Camp Willows jusqu'au quai extérieur de Victoria, d'une distance d'environ six kilomètres. Quand ils arrivèrent au centre-ville de Victoria, ils prirent une pause au coin des rues Fort et Quadra, puis Boisvert et sa section refusèrent de marcher. Le commandant, le lieutenant-colonel Albert "Dolly" Swift, insista. Boisvert refusa et son camarade donna un coup de poing au chapelain Catholique du bataillon. Swift tira alors son revolver aux pieds de Boisvert, et ce dernier cria « On y vas pas en Sibérie! »4

Pour supprimer la mutinerie, Swift ordonna les bénévoles de Toronto et de Kingston, qui appartenaient aux Compagnies A et B du 259e Bataillon et étaient toujours obéissants, d'enlever leur ceinture et de fouetter Boisvert et les mutins. « Ils l'ont fait de bonne volonté et nous procédâmes, ils furent surveillé plus attentivement que n'importe-quel groupe de prisonniers allemands », écrira plus tard un lieutenant à sa femme.5 Une « garde d'honneur » (cinquante soldats armés de baïonnette) fut convoquée pour escorter les mutins vers le navire à pointe de baïonnette.

23 heures plus tard le 259e Bataillon fut finalement à bord du SS Teesta, où Boisvert fut menotté avec une douzaine de mutins dans la cale du navire. Ils eurent le droit ni de prendre de douche ni de changer leurs vêtements pour 38 jours, quand Boisvert fut jugé par cour martiale et condamné à deux ans de travaux forcés pour crime de « se joindre à la mutinerie lorsqu'il servit les forces armées de Sa Majesté. » Le matin du 22 décembre 1918, Onil Boisvert et le 259e Bataillon de la Force Expéditionnaire canadienne (en Sibérie) partirent du port de Victoria pour Vladivostok

Le Protesilaus

Cinq jours derrière le SS Teesta, le paquebot « Blue Funnel » SS Protesilaus quitta Victoria avec 1800 troupes et 170 officiers. Le navire fut rénovées précipitamment pour accueillir les 2000 soldats — la moitié furent logés dans des couchettes tandis que le reste dormaient dans des hamacs suspendus aléatoirement sous le pont. Les conditions à bord du Protesilaus — qui mena à la création d'une Commission d'Enquête par le commandement militaire canadien — furent décris dans un poème satirique par la poète ouvrier Dawn Fraser, un pharmacien de Saint John, Nouveau-Brunswick, et volontaire du 260e Bataillon:

An over-loaded stomach, or may-be it was fear,

My hammock tossing wildly, my head was feeling queer;

The boat was tipping madly, the breakers fairly screamed;

I have no idea what time it was, I fell asleep and dreamed.

That the old Protesilaus dumped us out, along with all her crew,

And we struggled vainly, vainly, in an Ocean made of Stew.6– "Boulion à la SS Protesilaus," Dawn Fraser, de Songs of Siberia and Rhymes of the Road (1919)

Archives de la Colombie-Britannique, I-78247 / HP018920

SS Protesilaus quittant Victoria, le 26 décembre 1918. En mer, un soldat et un membre de l'équipage moururent d'accidents et le navire perdit son hélice après s'être coincé dans les glaces au nord du Pacifique.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Les conditions du voyage furent difficiles pour les troupes. Le navire fut surchargé et lutta contre le mauvais temps de Victoria jusqu'à Vladivostok, et le 30 décembre 1918, quatre jours après son départ, le navire affronta une violente tempête. Le soldat Harold Butler fut tué et deux autres blessés lorsqu'une grosse caisse de glace et de viande s'est détachée de ses supports et les écrasèrent . « C'était dégoutant », nota le lieutenant Stuart Tompkins.7

Deux jours plus tard, un membre d'équipage chinois périt lorsqu'il tomba à la mer lors d'une tempête. Comme le navire s'approcha de la Russie il rencontra d'autre mauvais temps, perdit son hélice et fut pris dans de la glace à cinquante kilomètres est de Vladivostok. Le Protesilaus envoya un message SOS par radio. Quand ces nouvelles atteignirent Vladivostok, deux croiseurs britanniques furent préparés, mais le Protesilaus envoya un deuxième message notant qu'ils n'avaient « pas besoin d'aide. » Le capitaine Eric Elkington se rappela soixante et dix ans plus tard: « Nous fûmes sauvés par un navire de guerre japonais. »8

Le Protesilaus navigua vers Vladivostok avec seulement une hélice.

Notes

- 1 Mark Osborne Humphries, “The Horror at Home: The Canadian Military and the ‘Great’ Influenza Pandemic of 1918,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 16, 1 (2005): 235-60.

- 2 White to Borden (via Sir Edward Kemp, overseas minister), 14 November 1918, Library and Archives Canada, Borden Papers, MG 26, ser. H1(a), vol. 103.

- 3 Borden to White, 7 December 1918, Library and Archives Canada, RG 24, ser. C-1-A, vol. 2557, file HQC-2514 (vol. 1).

- 4 Testimony of Major Guy Boyer, Lieutenant T.J. Morin, Captain G.N. Oliver, Lieutenant L.H.G. Van Boren, Sergeant R. Belleau, Captain S.M. Rapin, “Trial of No. 3312133 Rifleman Arthur Roy,” 28 January 1919, “Summary of Evidence for the Trial of No. 3312133, Rfn. Arthur Roy,” 27 December 1918, and “Schedule No. 3312133, Rfn. Arthur Roy” (all in Library and Archives Canada, RG 24, ser. C-1-A, vol. 1992, file H-Q-762-11-10, “Courts Martial in CEF [Siberia]”).

- 5 “What a Muddle,” BC Federationist, 28 February 1919.

- 6 “Boulion a là SS Protesilaus,” in Dawn Fraser, Songs of Siberia and Rhymes of the Road (Glace Bay, NS: Eastern Publishing, c. 1919), 21. See also “No. 254 Court of Inquiry,” 26 March 1919, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), Daily Routine Orders, March 1919, app. 41, p. 26.

- 7 Tompkins to Edna, 30 December 1918, reprinted in Stuart Ramsey Tompkins, A Canadian’s Road to Russia: Letters from the Great War Decade, ed. Doris H. Pieroth (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1989), 364. See also Ardagh Diary entry, 3 January 1919, LAC, Ardagh Fonds, MG 30, E-150, file 1/6; War Diary of 16th Infantry Brigade Headquarters CEF(S), 30 December 1918.

- 8 Eric Henry William Elkington interview, 24 January 1986, University of Victoria Special Collections, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 170.

Sauter à

Мобилизация и бунт

Коллекция Сидней Роджера, Бимсвилль, Канада

Франко-канадские призывники на собрание «Руки прочь от России» в г. Виктория, 13 декабря 1918 г. Этот диалог между солдатами из Квебека и рабочими Британской Колумбии способствовал восстанию 21 декабря.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

21 декабря 1918 г. франко-канадские солдаты подняли мятеж на улицах г. Виктория, провинция Британская Колумбия. Призывники 259-ого батальона Канадских экспедиционных сил в Сибири выходили из военного строя во время марша из лагеря Уиллоус на корабль Тееста для отплытия во Владивосток. На углу улиц Форт и Куадра 23-летний стрелок из Монреаля Ониль Бойсверт, демонстративно прокричал «On y va pas à Siberia!» («Я не хочу в Сибирь!»).

Две роты отказались идти маршем к кораблю. Неповиновение было подавлено, когда офицеры открыли стрельбу из револьверов, а лояльные солдаты использовали ремни в качестве хлыстов для возвращения мятежников в строй. Солдаты держали штыки наготове все 23 часа пока шла посадка на Теесту в верфи Дальней. Стрелок Бойсверт и десяток других предводителей мятежа были закованы в кандалы в корабельной тюрьме на протяжении трех недель плавания до Владивостока.

Что привело к таким беспокойствам?

Мобилизация Сибирских сил

Библиотека и Архивы Канады, Имперская коллекция масляных картин, 1972-026, IC-31

«Войска в Петевава: Канадские войска маршируют в Сибирь», - рисунок К.В. Джеффриса, 1918 г.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

12 августа 1918г. Канадский Тайный совет одобрил указ PC-1983о составе К анадских экспедиционных сил в Сибири, которые состояли из 4209 мужчин и одной женщины - старшей медсестры Грейс Элриды Поттер. По дипломатическому стечению обстоятельств два британских полка (Мидэлэхсес и Хамшир), численностью в 1500 чел. были переданы под командование канадского генерал-майора Джеймса Элмслея.

Канадские экспедиционные силы для Сибири состояли из военных из каждой провинции. Состав экспедиционных сил был следующим: два пехотных батальона Шестнадцатой канадской пехотной бригады, артиллерийские войска, инженерная рота, два небольших соединения из пекарей, мясников, медиков и других работников тыла. Двести человек представляли Королевскую северо-западную конную полицию, вместе с которыми во Владивосток были также доставлены триста лошадей.

Одна третья всех канадских войск состояла из призывников, созванных служить по военно-призывному акту от 1917 г.. Мобилизация совпала с Днем перемирия (11 ноября 1918 г.), что ознаменовало конец сражений на Западном фронте, а также совпала с эпидемией «Испанки», которая принесла большие смерти, как военным, так и гражданскому населению во всем мире, в том числе и в Канаде. Все военные части дислоцировались в казармах г. Виктория, Нью-Вестминстер и Коквитлам в Британской Колумбии, где возмущения военных были подогреты местными рабочими радикалами и затем перешли в мятеж.

Объединение военных сил в лагере Уиллоус

Коллекция Сиднея Роджера, г. Бимсвилль, Канада

Вид Скалистых гор с Канадской тихоокеанской железной дороги, октябрь 1918 г. «Испанка» была привезена на западное побережье Канады именно этими поездами с канадскими военными, призванными для отправки в Сибирь.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

Мобилизация войск на западном побережье проходила в момент тяжелых потерь Канады на фронте в Европе: почти 6 000 человек погибло на западном фронте в сентябре и октябре 1918 г. В связи с тем, что поток волонтеров для отправке в Сибирь завершился, было решено набирать призывников в соответствии с актом об обязательной воинской повинности. Было призвано 1653 чел. для экспедиционных сил.

259-ый батальон (канадские стрелки) был под командованием лейтенант-полковника Альберта Свифт (Долли), который создал батальонные подразделения в Монреале. Батальон состоял из:

- Рота A – военный округ г. Торонто

- Рота B – военные округа г. Лондона и г. Кингстона

- Рота С – военный округ г. Монреаль

- Рота D – военный округ г. Квебек

260-ый батальон (канадские стрелки) был под командованием лейтенант-полковника Ф.С. Джемьесона и состоял из:

- Рота А – Новая Шотландия и Нью-Брансуик

- Рота B - Манитоба

- Рота С – Саскачеван и Альберта

- Рота D – Британская Колумбия

Коллекция Джона Скьюса, Канадские экспедиционные силы в Сибири 1918-1919 гг. (Оттава, доступно для исторических публикаций, 1990 г.)

Под брезентом в Коквитламе, Британская Колумбия, Ноябрь 1918 г.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

Канадские экспедиционные силы были мобилизованы в момент, когда «испанка» добралась до Канады; вирус гриппа привел к смерти 60 млн. человек по всему миру, 101 чел. умерло в г. Виктория, 2800 чел. были им заражены. Недавнее исследование показало, что «испанка» попала на западное побережье Канады на поезде с канадскими военными, призванными для службы в Сибири. Медицинские записи госпиталей в городах Виннипег, Калгари и Ванкувер показывают, что первые засвидетельствованные случаи заболевания возникали в считанные часы после того, как поезда с военными Канадских экспедиционных сил проходили через города.1

Канадский военный музей, архивная коллекция Джорджа Меткалфа

Канадские солдаты в койках, Королевский парк, Новый Вестминстер, БК, октябрь 1918 г.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

В Британской Колумбии несколько частей были размещены в палатках под г. Кокитлам, восточнее Ванкувера, тогда как другие части, включая конную полицию, базировались в казармах Королевского парка в Новом Вестминстере. Но главные силы, приблизительно 3000 чел. были переправлены морем в г. Виктория, где они и разместились в лагере Уиллоус.

Перемирие и волнения

Через неделю после того, как военные пришли на западное побережье Канады, в Европе было подписано перемирие; четырехлетняя война закончилась. С подписанием перемирия, канадская оппозиция, выступающая против интервенции в Сибирь, возросла. Эта оппозиция была представлена многими: от министерских министров до фермерских организаций (Объединенные фермеры Онтарио); за отмену интервенции выступали рабочие советы четырех крупных канадских городов и сами солдаты экспедиционных сил.

Библиотека и Архивы Канады, коллекция Дороти Перрин, e010752824

Осмотр 258-ого батальона в лагере Уиллоус, г. Виктория, декабрь 1918 г. как сообщал «Дэйли Таймс»: «Это, возможно, не самое лучшее время года для пребывания в Виктории военнослужащих… В последнее время их пребывания было отмечено много осадков в виде дождя, который развел море грязи в лагере Уиллоус».

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

Сочетание влажной осени Британской Колумбии и эпидемии «испанки» создало взрывоопасную ситуацию.

Когда Р. Боден плыл через Атлантику в Европу для мирных переговоров, он получил срочную телеграмму от исполняющего обязанности премьер-министра сэра Томаса Уайта (первая в длинном ряду телеграмма, предшествовавшая отправке войск в Россию):

«Все наши коллеги полагают, что общественное мнение Канады не будет поддерживать нас в дальнейшей отправке войск, которые в большинстве состоят из призывников времен войны, которая уже закончилась. Мы все считаем, что не следует больше отправлять в Сибирь какие-либо дополнительное войска, а уже имеющиеся, должны вернуться домой сразу, как позволит ситуация. Прошу Вас рассмотреть это с надлежащей тщательностью»2

Премьер-министр Боден проигнорировал советы своих министров и постановил, что миссия будет продолжаться, не смотря на перемирие в Европе.

Очерк

Стрелок Ониль Бойсверт и мятеж в Виктории 21 декабря 1918 г.

Коллекция Карел Менард, Монреаль, Квебек

Стрелок Ониль Бойсверт, один из солдат Квебека, осужденных за мятеж в г. Виктории, c. осенью 1918 г.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

Коллекция семьи Болье, г. Какоуна, пров. Квебек

Рота «D» 259-ого батальона в лагере Уиллоус до отправки в Сибирь, декабрь 1918г. эта рота была мобилизована из военного округа г. Квебек и стала оплотом несогласия. Несколько солдат были позже преданы военно-полевому суду за участие в мятеже в г. Виктория 21 октября 1918 г.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

Летом 1918г. Ониль Бойсверт был призван в канадскую армию по закону о воинской повинности, весьма спорного закона, которые спровоцировал беспорядки в Квебеке. Будучи фермером из города Драммонд он был прикреплен к роте «C» 259-ого батальона в Монреале, располагающейся в казармах на Пил-стрит. Бойсверт был госпитализирован из-за «испанки», затем все его подразделение было переведено на карантин. А уже в конце октября 1918 г. Бойсверт с ротой «С» были в пути вдоль канадской тихоокеанской железной дороги на пути в Британскую Колумбию.

Коллекция Джорджа Меткафа, Канадский военный музей

Генерал-майор С.Леки инспектирует солдат 259-ого батальона лагеря Уиллоус, г. Виктория, декабрь 1918 г.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

Ониль Бойсверт был расквартирован в лагере Уиллоус, г. Виктория, когда мокрая осень Британской Колумбии и пришедшая эпидемия «испанки» подорвали моральный дух экспедиционных сил. Военные стали посещать многие митинги протеста рабочих , в которых ораторы от Социалистической партии Канады и Федеральной Лейбористской партии издали требование «Руки прочь от России».

Коллекция Сидни Роджера, г. Бимсвилл, Онтарио, Канада

Солдаты 259-ого батальона в центре г. Виктория, декабрь 1918г. Публичные собрания были запрещены городским комитетом по здоровью, в попытке обуздать эпидемию гриппа. Когда запрет был снят, солдаты в полной мере использовали свое свободное время.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

Коллекция Сидни Роджера, г. Бимсвилл, Онтарио, Канада

Франко-канадские призывники из 259-ого батальона на митинге «Руки прочь от России», Театр Колумбия, г. Виктория, 13 декабря 1918.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

Несмотря на усилия военного командования свести на нет влияние рабочих собраний, недовольство росло. Когда Бойсверту (как и его товарищам по взводу) предложили стать волонтером для службы в Сибири он отказался: «как фермер, я больше полезен дома». Будучи уже призывником, он вместе с 300 другими соратниками написал срочную телеграмму в Оттаву с просьбой не отправлять их в Сибирь. Однако сославшись на обязательства данные Британскому правительству и «определенным доброжелательным лицам в России» правительство Роберта Бодена постановило о направление данных призывников во Владивосток.3

Архив Британской Колумбии, I-78248/ HP018921

Солдаты марширующие к верви Райсет, г. Виктория, декабрь 1918 г.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

BПеред рассветом самого короткого дня в году – 21 декабря 1918 г. Бойсверт и другие франко-канадские призывники 259-ого батальона были внезапно разбужены в своих палатках приказом, следовать из лагеря Уиллоус в самую дальнею верфь г. Виктория, рассоложенную в шести километрах. Когда они достигли центра Виктории, и сделали обычный перерыв на углу улиц Форт и Куадра, Бойсверт и его взвод отказались идти далее. Командующий лейтенант-полковник Альберт Свифт (Долли) приказал призывникам продолжить движение. Бойсверт отказался, поскольку один рядовой ударил католического священника его батальона кулаком. На это неповиновение Свифт выстрелил Бойсверту в ногу, от боли он прокричал: «Я не хочу в Сибирь!». 4

Для подавления мятежа, Свифт командовал лояльным частям, волонтерам из Торонто и Кингстона, применить свои кожаные ремни, чтобы вернуть Бойсверта и других мятежников в строй. «Они делали это с такой волей, что нам ничего не оставалось, как продолжить путь, те волонтеры были столь тесно сплочены между собой, как никакие немецкие военнопленные, которых я когда-либо видал», - позже писал в письме лейтенант Бойсверт жене.5 Почетный караул (пятьдесят военных со штыками) были вызваны для сопровождения мятежников к кораблю.

Путь занял 23 часа только для того, чтобы перевести 259-ый батальон к кораблю «Тееста», где Бойсверта и десяток других зачинщиков заковали в наручники в трюме судна. Им не разрешали пользоваться душем и переодеваться в течение 38 дней, после чего Бойсверт был передан военно-полевому суду и приговорен к двум годам каторжным работ по обвинению в «участие в мятеже в качестве военнообязанного армии Его Величества». Ранним утром 22 декабря 1918г. Ониль Бойсверт и 259-ый батальон Канадских экспедиционных сил в Сибири отплыл из Виктории во Владивосток.

«Протесилаус»

Через пять дней после отплытия «Теесты» лайнер «Протесилаус» отдал швартовы в Виктории с дополнительными 1800 солдатами и 170 офицерами. Пассажирский лайнер спешно модернизировали для размещения 2000 солдат, одна половина которых спала на нарах, другая в гамаках, беспорядочно расположенных на нижней палубе. Условия на борту впоследствии обсуждались в суде, инициированном членами команды. Сатирическая поэма пролетарского поэта Дона Фрейзера (волонтер 260-ого батальона) хорошо передает обстановку на корабле:

Тяжесть в животе от еды иль от страха,

Гамак бросало в стороны, что в голове шли мысли странные,

Лодку трясло жутко, люди в трюмах кричали,

Понятие не было о часе идущем, лишь снился мне сон.

О том, как бросил нас старый корабль со всем экипажем,

А мы боролись напрасно, напрасно в бушующем море.6– (дословный перевод) "Boulion à la SS Protesilaus," Dawn Fraser, from Songs of Siberia and Rhymes of the Road (1919)

Архив Британской Колумбии, I-78247 / HP018920

Судно «Протесилаус» перед отплытием из г. Виктория, 26 декабря 1918. В море, один солдат и один член экипажа погибли в результате несчастных случаев, а корабль потерял свой винт, когда застрял во льдах северной части Тихого океана.

Смотрите больше фотографий в архиве

В море условия были очень зловещими. Корабль был сильно перегружен и боролся со стихией весь путь, вплоть до Владивостока. 30 декабря 1918г., через четыре дня после отплытия, судно попало в шторм. Рядовой Герольд Батлер погиб, а два других солдата получили ранения, когда большой кусок льда вонзился с борт. По рассказу лейтенанта Стюарта Томпкинса — «это было жутко».7

Спустя два дня, член экипажа китайского происхождения упал за борт во время шторма и погиб. Когда корабль подошел к России, опять настала плохая погода и судно теряет гребной винт и застревает во льдах в пятидесяти километрах к востоку от Владивостока. «Протесилаус» послал сообщение SOS по телеграфу. Когда его получили во Владивостоке два британских крейсера пошли на помощь. Тем не менее, «Протесилаус» послал вторую радиотелеграмму с его местоположением и сообщением: «помощи не требуется». Капитан Эрик Элкингтон вспоминал семь лет спустя, что «час спас японский военный корабль».8

«Протесилаус» доплыл до Владивостока тихим ходом с одним винтом.

Примечания

- 1 Mark Osborne Humphries, « The Horror at Home: The Canadian Military and the ‘Great’ Influenza Pandemic of 1918 », Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 16, 1 (2005): 235-60.

- 2 White à Borden (via Sir Edward Kemp, Ministre d'outre-mer), 14 novembre 1918, Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, Borden Papers, MG 26,ser. H1(a), vol. 103.

- 3 Borden à White, 7 décembre 1918, Bibliothèque et Archives de Canada, RG 24, sér. C-1-A, vol. 2557, dossier HQC-2514 (vol. 1).

- 4 Témoignage de Major Guy Boyer, Lieutenant T.J. Morin, Capitaine G.N. Oliver, Lieutenant L.H.G. Van Boren, Sergent R. Belleau, Capitaine S.M. Rapin, « Trial of No. 3312133 Rifleman Arthur Roy », 28 janvier 1919, « Summary of Evidence for the Trial of No. 3312133, Rfn. Arthur Roy », 27 décembre 1918, et « Schedule No. 3312133, Rfn. Arthur Roy » (au Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, RG 24, Ser. C-1-A, vol. 1992, dossier de l'AC-762-11-10,« Courts Martial in CEF [Siberia] »).

- 5 « What a Muddle », BC Federationist, le 28 février 1919.

- 6 « Boulion a là SS Protesilaus », dans Dawn Fraser, Songs of Siberia and Rhymes of the Road (Glace Bay, NS: Eastern Publishing, c. 1919), 21. Aussi « No. 254 Court of Inquiry », 26 mars 1919, « War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), Daily Routine Orders », mars 1919, app. 41, p. 26.

- 7 Tompkins à Edna, 30 décembre 1918, reproduit dans Stuart Ramsey Tompkins, A Canadian’s Road to Russia: Letters from the Great War Decade, ed. Doris H. Pieroth (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1989), 364. Aussi « Ardagh Diary » du 3 janvier 1919, BAC, Ardagh Fonds, MG 30, E-150, dossier 1 / 6; « War Diary of 16th Infantry Brigade Headquarters CEF(S) », 30 décembre 1918.

- 8 Interview de Eric Henry William Elkington, le 24 janvier 1986, University of Victoria Special Collections, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 170.

Перейти к

Research Question

Why did the French-Canadians in the 259th Battalion mutiny in the streets of Victoria, British Columbia the day they deployed for Vladivostok?

Key Themes

- • French-Canadian antipathy to the Military Service Act

- • Class tensions within the armed forces

- • Working-class responses to the Russian Revolution and Siberian Expedition

- • War-time social unrest related to conscription, the high cost of living, and the Spanish Flu

Question de recherche

Pourquoi les Canadiens-français du 259e Bataillon se mutinèrent dans les rues de Victoria en Colombie-Britannique le jour de leurs déploiement pour Vladivostok?

Principaux thèmes

- • Antipathie canadienne-française contre l'Acte de Service Militaire

- • Tensions entre classes dans les forces armées

- • Réactions d'ouvriers à la Révolution russe et à l'expédition en Sibérie

- • Dissensions sociales pendant la Première Guerre causé par la conscription, la vie chère et la grippe espagnole

Исследуемый вопрос

Почему франко-канадцы 259-ого батальона подняли мятеж на улицах Виктории в день отплытия во Владивосток?

Ключевые темы

- • неприятие франко-канадцами Акта об обязательной воинской повинности

- • классовое напряжение в рядах армии

- • реакция рабочего класса на Октябрьскую революцию в России и на интервенцию в Сибирь

- • социальные протест против военно-призывной системы, высокая стоимость жизни, вирус «испанки»

Maps

Primary Documents

- Privy Council Order-in-Council 1983, authorizing the CEFS (coming soon)

- Composition of CEFS

- Military Service Act, 1917

- Protest resolution from 300 "loyal French Canadians"

- Letter from Victoria Trades and Labor Council to Minister of Militia and Defence

- BC Federationist newspaper report on dissent at the Willows Camp (coming soon)

- Semi-Weekly Tribune report on "Hands Off Russia" meeting (coming soon)

- Lieutenant's eye-witness account of the Victoria Mutiny

- Affidavit sworn by Onil Boisvert (coming soon)

- Testimony from officers at the court martial of Arthur Roy (coming soon)

- Stuart Tompkins letter on dissent among the troops (coming soon)

- Johnny Côté's memoir "Un noël en mer" on the crossing of the SS Teesta

- Eric Elkington's diary on the crossing of the SS Protesilaus

Multi-media

- Video of route of march of 259th Battalion, 2010 (coming soon)

- Eric Elkington interview on SS Protesilaus

Photos from the Digital Archive

Plans

Documents primaire

- Décret en conseil du Conseil Privé 1983, autorisant la FECS

- Composition du FECS

- Acte de Service Militaire, 1917

- Résolution de la protestation de 300 « Canadiens-français loyaux »

- Lettre du Conseil de la Main d'œuvres et des Métiers de Victoria au Ministère de la Milice et la Défense

- Rapport du journal BC Federationist sur la dissidence au Camp Willows

- Rapport du Semi-Weekly Tribune sur la réunion « Hands Off Russia »

- Témoignage d'un Lieutenant sur la mutinerie de Victoria

- Déclaration officielle d'Onil Boisvert

- Témoignage d'officiers devant la cour martiale d'Arthur Roy

- Lettre de Stuart Tompkins sur l'insubordination des troupes

- Le mémoire de Johnny Côté « Un noël en mer » sur le passage de la SS Teesta

- Le journal d'Eric Elkington pendant la traversée du SS Protesilaus

Multimédia

Photos d'archives numériques

Карта

Первичные источники

- Указ Тайного совета №1983 о формировании Канадских экспедиционных сил для отправки в Сибирь (скоро)

- состав экспедиционных сил

- указ о воинской повинности, 1917 г.

- резолюция протеста 300 «преданных франко-канадцев»

- письмо от рабочих Виктории министру милиции и оборону

- статья газеты «Федерэйшионист» (Британская Колумбия) о инакомыслящих в лагере Уиллоус (скоро)

- статья в ежедневнике Трибуна: «Руки прочь от России» (скоро) (скоро)

- свидетельство мятежа в Виктории (скоро)

- письменное посягательство перед присягой Онила Бойсверта (скоро)

- Свидетельские показания офицеров на суде по военному Артуру Рою (скоро)

- пиьсмо Стюарта Томпкинса домой о бунтовщиках среди военных (скоро)

- Мемуары Джонни Коте «Рождество на море» на прохождение «Тееста»

- записи дневника Эрика Элкингстона во время плавания на «Протеселаусе»

Мультимедиа

- Видео о пути следования 259-ого батальона, 2010 г. (скоро)

- интервью Эрика Элкингстона на «Протесилаусе»

English

English Français

Français Русский

Русский