Evacuation

The Canadians evacuated Vladivostok on four ships between May and June 1919. Before leaving, a memorial stone was commemorated at the Marine Cemetery on Monastirskaia Hill southeast of the city, alongside the graves of fourteen soldiers who died in Vladivostok. One of these soldiers was Private Edwin Stephenson, an Anglican priest in peacetime who served as a medic with the advance party to Omsk. Stephenson contracted small pox on his return to Vladivostok, dying at the Second River Hospital a week before his ship was scheduled to sail home. Five other soldiers had died at sea.

Robert McNay Collection, Katrine, Ontario

Canadian soldiers boarding the SS Empress of Russia for the journey home from Vladivostok, 19 May 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Back in British Columbia, two more soldiers died while in quarantine at the William Head Quarantine Station near Victoria. The Canadians returned to a country divided along the lines of social class, as general strikes paralyzed production from Victoria to Winnipeg to Amherst, Nova Scotia. The story of the Siberian Expedition — Canada's first foray in the Far East — was quietly forgotten.

Stephenson Family Collection, Burlington, Ontario

Two Canadian officers stand beside recently prepared graves at the Canadian and British plot in the Marine Cemetery outside of Vladivostok, 1 June 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Opposition on the Home Front

Before the main body of Canada’s Siberian Expeditionary Force had embarked for Russia, the military command warned the Borden Cabinet:

“that arrangements in Siberia lack co-ordination and control, that the railway system is in a condition seriously disorganized, that among Allies there is no general agreement, that Americans are inactive, that the Japanese, bent on commercial penetration, are subsidizing insurgent elements.”

This proved to be a prescient warning, anticipating the failure of Canada’s Siberian Expedition. In February 1919, the government grudgingly reversed course, ordering the evacuation of all units to Canada “on the first available ships.”1

The prime minister's decision to evacuate reflected unstable conditions in Russia, but also widespread public opposition in Canada to the Siberian Expedition. Working-class opposition had contributed to the Victoria Mutiny, as Canadian socialists expressed strong sympathies with the Russian Bolsheviks. These tensions expanded as the main body of the force sailed for Vladivostok.

The labour councils of Canada's four largest cities — Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, and Montreal — went on record opposing the Siberian Expedition. They were joined by farmer organizations including the United Farmers of Ontario and the Mount Hope Grain Growers Association in Saskatchewan. In militia and defence minister Sydney Mewburn's Hamilton riding, the business-aligned Herald and Spectator newspapers questioned the wisdom of deploying the force, declaring that “outsiders really have no right to interfere” in Russia's internal affairs.2 This followed earlier criticism in the Toronto Globe newspaper.

Opposition to the Siberian Expedition extended into the House of Commons in Ottawa. At a public meeting in March 1919, Dr Hermas Deslauriers, MP for the Montreal riding of St-Mary, declared that the Siberian Expedition "should ... be considered a crime." Another Quebec MP, Edmund William Tobin of Richmond-Wolfe, asked the Defence Minister: "how many men enlisted under the provisions of the Military Service Act, 1917, were dispatched for Siberia" and under "what law, Order in Council or other authority said men were sent to Siberia."3

As these questions arose over the legality of deploying "MSA Men" for service in Russia, General Elmsley quietly suspended the sentences of the Quebecois conscripts "convicted of mutiny at Victoria."4

The Fallen

Stephenson Family Collection, Burlington, Ontario

Canadian chaplains Harold McClausland and Jacques Oliviere, joined by other Canadian officers, at the dedication of the Canadian Memorial, Marine Cemetery, Vladivostok, Russia, 1 June 1919. Fourteen Canadians are buried at the site.

View more photos like this in the archive

By June 1919, the Canadians had returned home, with the exception of nineteen soldiers who died in Russia or perished at sea, and five Canadian soldiers who deserted in Russia. The Canadian command dedicated fourteen wooden crosses and a stone monument at Vladivostok's Marine Cemetery on Monastirskaia Hill, in a ceremony on 1 June 1919 officiated by Capts. Harold McCausland and Jacques Oliver, the Anglican and Catholic chaplains of the Canadian force.

Three other soldiers who died on the journey to Vladivostok were buried at sea. Four soldiers who died on the trip home are buried at cemeteries in William Head, British Columbia, Canada; Ruthven, Ontario, Canada; and Canton, Ohio, in the United States of America.

Buried at Vladivostok Marine Cemetery

- Lieut. Alfred H. Thring, 260th Btn, committed suicide on the Gornostai Road, 18 March 1919

- Pte. Walter Boston, 16th Field Ambulance, died of endocarditis, 16 April 1919

- Rfn. William Edward Dodd, 260th Btn, died of toxaemia, 5 April 1919

- Rfn. Earl Gillespie, 260th Btn, died of spinal meningitis, 14 March 1919

- Rfn. David Higgins, 260th Btn, died of periocarditis, 6 March 1919

- Rfn. Romeo Lariviere, 259th Btn, died of pneumonia, 11 March 1919

- Rfn. James Florence Manion, 260th Btn, died of pneumonia, 22 February 1919

- Rfn. Joseph Emmett McDonald, 259th Btn, died of pneumonia, 28 February 1919

- Rfn. Roy Sothern, 260th Btn, died of pneumonia, 4 March 1919

- Pte. Edwin Howard Stephenson, 11th Stationary Hospital, died of small pox, 23 May 1919

- Gunner Frederic Eaton Ward, 20th Machine Gun Co., died of pneumonia and scarlet fever, 3 March 1919

- A/QMS Ernest Worthington, Base H.Q., died of pneumonia, 6 March 1919

- Sgt. John Shirley Murray Wynn, 16th Field Co. (Engineers), died of exposure, 14 January 1919

Buried at Sea

- Pte. Edward Biddle, Base Guard, died of influenza aboard the SS Empress of Japan, 22 October 1918

- Rfn. Harold Leo Butler, 259th Btn, died in an accident aboard the SS Protesilaus, 31 December 1918

- Rfn. Frank Joseph Kay, 259th Btn, died in an accident aboard the SS Teesta, 28 December 1918

Buried at William Head cemetery,

Metchosin, British Columbia, Canada

- Pte. Richard Leonard Massey, No. 9 Detachment COC, died of small pox, 30 May 1919

- Rfn. Peter Roy McMillan, 259th Btn, died of small pox, 6 June 1919

Buried at Ruthven United Cemetery,

Essex County, Ontario, Canada

- Pte. Wilfred Charles Lane, Force H.Q., died of pneunomia at Hong Kong, 10 March 1919

Buried at West Lawn Cemetery,

Canton, Ohio, USA

- L/Cpl. George H. Buckwalter, 20th Machine Gun Co., died of pneumonia aboard the SS Monteagle, 25 April 1919

PROFILE

Pte. Edwin Howard Stephenson, 1886-1919

Stephenson Family Collection, Burlington, Ontario

Edwin Stephenson, the day he was ordained as an Anglican Priest, Desboro, Ontario, 26 May 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

Edwin Howard Stephenson was born in April 1886 in Tillsonburg, Ontario. He entered the clergy of the Anglican Church and worked in the village of Desboro during the early years of the First World War. Stephenson was ordained as a priest on 21 May 1918. The next day, he enlisted in the Canadian Army as a non-combatant soldier: a medic in the Canadian Army Medical Corp.

With the formation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Siberia) in August 1918, Pte. Stephenson was attached to the 11th Stationary Hospital. He sailed to Vladivostok with the Advance Party aboard the Empress of Asia in October 1918. In December 1918, Stephenson travelled "up county" — part of the 55-member Canadian advance party to Omsk. He was one of the very few Canadian to ever reach the Siberian interior.

Stephenson Family Collection, Burlington, Ontario

Private Edwin Stephenson, Canadian Army Medical Corps, c. autumn 1918.

View more photos like this in the archive

Stephenson compiled a fascinating album of photographs along the Trans-Siberian Railroad, depicting the scenery, villages, and people along the track, as well as bridges blown up by the partisans. He spent the winter of 1918-19 in Kolchak's capital city, awaiting the main body of the Canadian force (which never arrived). In April, Stephenson evacuated Omsk with the Canadian party.

Stephenson Family Collection, Burlington, Ontario

Private Edwin Stephenson with a group of boys at the Vladivostok Chinese market, prior to his death from small pox.

View more photos like this in the archive

Edwin Stephenson returned to Vladivostok as the Canadian government scrambled to find ships to bring the 4,200 troops home. While awaiting evacuation, he contracted small pox and died at the Second River Hospital on 24 May 1919.

Stephenson was buried alongside thirteen other Canadians and fourteen British troops at the Vladivostok Marine Cemetery, adjacent to the plot for the fallen Czecho-Slovak, French, and Japanese soldiers. His grave was marked with a plain wooden cross and commemorated by the Canadian command on 1 June 1919.

In the 1990s, as the Cold War ended and Vladivostok once again opened to foreigners, a granite tombstone was erected by a Canadian naval party. No family member has had the opportunity to visit Edwin Stephenson's final resting place. Many thanks to Gwen Stephenson of Burlington, Ontario, for sharing her uncle Edwin's photographs and diary.

Stephenson Family Collection, Burlington, Ontario

Private Edwin Stephenson’s grave, Vladivostok Marine Cemetery, c. May 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Photograph by Benjamin Isitt

Edwin Stephenson’s grave, Vladivostok Marine Cemetery, 2008.

View more photos like this in the archive

Aftermath

Canada's Visual History

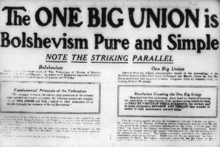

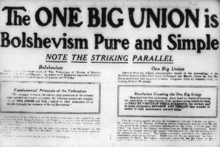

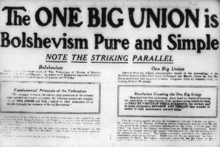

Anti-OBU advertisement, published in the midst of the Winnipeg General Strike as the OBU sunk roots among Canadian workers and sympathy strikes erupted from Victoria to Amherst, Nova Scotia. c. May 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Addressing Parliament on 10 June 1919, Dr Henry Sévérin Béland, Member of Parliament for Beauce, declared: "This expedition was a political error, a military mistake, and a wanton extravagance."5 Béland, a war hero who had been released from a German prisoner-of-war camp, expressed a widely held view in Canada. He made his remarks in the midst of the most profound industrial crisis in Canada's history.

The wave of industrial unrest extended from the West Coast to Nova Scotia, where workers at the Canadian Car and Foundry Company and other plants in Amherst struck for the One Big Union. General Elmsley and the SS Monteagle reached strike-riddled Vancouver on 22 June with the remnants of Canada’s Siberian Expeditionary Force. One hundred and fifty Mounties from RNWMP “B” Squadron disembarked, to a barrage of bricks and stones from angry longshoremen, and were promptly ordered to serve strike duty.

Canada's Visual History

RNWMP officers charge down Main Street in Winnipeg on horseback, opening fire. Joined by regular Canadian soldiers in khaki, the authorities shot 50 strikers and killed two, breaking the back of the Winnipeg General Strike. "Bloody Saturday," 21 June 1919. The body of one of the two men killed, Mike Sokolowski, can be seen on the curb.

View more photos like this in the archive

“There appears to be no definite reason for [the strike] except [the] desire of alien agents, apparently in control of unions, to provoke class war throughout America and get control of all production in their own hands,” Lieutenant-Colonel Geoffrey McDonnell observed.6

Canada's Visual History

The Canadian military occupies Winnipeg, Canada's third largest city, bringing an end to one of the most forceful working-class challenges to the legitimacy of employers and the state in Canadian history. "Bloody Saturday," 21 June 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Back in Siberia and the Russian Far East, the Allied-White war effort collapsed. The Red Army seized Omsk in November as the last British forces evacuated. In January 1920, Vladivostok partisans toppled Kolchak's local military governor, General Pavel Ivanov-Rinov, in a bloodless coup. At Irkutsk, the mutinous Czechoslovak Legion surrendered Kolchak to local Red authorities, who executed the former White dictator by firing squad.

The Americans pulled out of Vladivostok in April 1920, followed by the Czechoslovaks in May, who sailed around the world to their new homeland. En route, they passed through Vancouver, fully armed, before boarding Canadian Pacific Railway trains for the East.

A two-year power struggle ensued in the Russian Far East, as an array of White and Red administrations alternated in power, alongside the anomolous Far Eastern Republic. Finally, on 25 October 1922, the last Japanese units evacuated Vladivostok as columns of Red Army troops entered the city. The Soviet Union extended from the Pacific and Arctic Oceans to the Caspian, Black, and Baltic Seas — holding power for the next seven decades.

In the years that followed Canada's evacuation of Vladivostok, the old wooden crosses on Monastirskaia Hill rotted through time and neglect, as red scares and cold wars severed the city from the wider world. After the Second World War, Soviet authorities declared Vladivostok a "closed city," denying access to foreigners to guard Russia's nuclear submarine fleet.

Photograph by Benjamin Isitt

Canadian monument at the Vladivostok Marine Cemetery, 2008. Fourteen Canadians are buried on this quiet hillside outside the city, alongside the graves of British, French, Czechoslovak, and Japanese troops.

View more photos like this in the archive

In the 1990s, as the Soviet Union dissolved and the West sought to restore influence in the Russian Far East, a Canadian naval party from the HMCS Protector travelled to Vladivostok, working for three weeks to restore the Canadian and British graves on Monastirskaia Hill. Canada’s parliamentary committee on foreign affairs had received evidence that:

"There are Canadian graves left in Vladivostok that are in a terrible shambles. Headstones have been stolen or knocked over. Graffiti has been painted on some of the headstones. It seems a shame that we forget about those."7

Canada's fallen soldiers were not the only casualties of this controversial moment in the country's past. In the words of a graduate thesis written fifty years ago, the Siberian Expedition itself became “only a memory for old soldiers.”8 Born out the chaotic geopolitical pressures of the First World War and Russian Revolution, the story of Canada's Siberian Expedition was forgotten. It is the task of new generations to remember this contested history.

For the full story, read the book

From Victoria to Vladivostok: Canada's Siberian Expedition

Notes

- 1 Lash to Mewburn, 3 December 1918, LAC, RG 24, ser. C-1-A, vol. 2557, file HQC-2514 (vol. 1); “Inquiry of the Ministry by Mr. Demers, No. 58, Orders of the Day No. 23,” 27 March 1919, LAC, RG 24, ser. C-1-a, vol. 1993, file 762-11-24, “Queries Relating to CEF (Siberia).”

- 2 Gordon Grey, “Canada and the Siberian Expedition,” The Nation (New York), 1 February 1919, 162-63; “Canadians in Russia,” Hamilton Herald, 13 December 1918

- 3 “Extract of Speech of Dr. Hermas Deslauriers, St-Mary Division, Montreal, 11 March 1919, LAC, RG 24, ser. C-1-A, vol. 2557, file HQC-2514 (vol. 2), “Situation in Russia – Allied Intervention in Russia”; Order of the House of Commons, 7 April 1919, LAC, RG 24, ser. C-1-a, vol. 1992, file HQ-762-11-27, “Inquiry House of Commons by Mr. Tobin.” See also Canada, Report of Debates of the House of Commons, 1 April 1919.

- 4 Defensor to Elmsley, 1 April 1919, Bickford to Headquarters CEF(S), 5 April 1919, Elmsley to Defensor, 10 April 1919 (all in LAC, RG 9, ser. III-A-3, vol. 373, file A3, SEF Force HQ MSA); Swift to Brigade Headquarters, 8 April 1919, Barclay to Elmsley, 11 April 1918, Barclay to Elmsley, 12 April 1919, “Suspension of Sentence,” 14 April 1919 (all in LAC, RG 9, ser. III-A-3, vol. 371, file A3, SEF Force HQ 23.

- 5 Canada, Report of Debates of the House of Commons, 10 June 1919, p. 3298.

- 6 The sympathetic strikes of spring 1919 are examined in Gregory S. Kealey, “1919: The Canadian Labour Revolt,” Labour/Le Travail, 13 (Spring 1984): 11-44; Alan Phillips, The Living Legend: The Story of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Toronto and Boston: Little, Brown, 1954), 86; Major G.F. Worsley Report on “B” Squadron RNWMP, 11 October 1919, LAC, RG 18, RCMP Collection, vol. 3179, file G 989-3 (vol. 2); Telegram “Empress of Russia,” n.d. [c. June 1919], Hoover Institution Archives, Geoffrey McDonnell Collection, acc. XX233-10 A-V.

- 7 Canada, Department of Foreign Affairs, “Evidence,” 30 May 1995, DEFA 25 Block 101, http://www.parl.gc.ca/35/Archives/committees351/defa/evidence/25_95-05-30/defa25_blk101.html (viewed 14 July 2008).

- 8 Steuart Beattie, “Canadian Intervention in Russia, 1918-1919” (MA thesis, McGill University, 1957), 409.

Go to

Évacuation

L'évacuation canadiens de Vladivostok prendra quatre navires entre mai et juin 1919. Avant de partir, une pierre commémorative fut érigée au cimetière marin de la colline Monastirskaia au sud-est de la ville, près des tombes de quatorze soldats morts à Vladivostok. Un de ces soldats fut Edwin Stephenson, un prêtre Anglican avant la guerre qui servi d'infirmier pendant l'expédition à Omsk. Stephenson contracta la variole, et mourra à l'hôpital « Second River » à Vladisvostok une semaine avant l'arrivé prévu de son navire pour le Canada. Cinq autres soldats périrent en mer.

Collection Robert McNay, Katrine, Ontario

Soldats canadiens à bord l'SS Empress of Russia en route pour le Canada, le 19 mai 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Lors du retour en Colombie-Britannique, deux autres soldats périrent dans la station de quarantaine de William Head, près de Victoria. Le pays qu'accueilli les troupes canadiennes fut comblé de divisions sociales. Une grève générale paralysa la production de Victoria à Winnipeg à Amherst, en Nouvelle-Écosse. L'histoire de l'expédition en Sibérie — la première incursion canadienne dans l'Extrême-Orient — fut largement oubliée.

Collection de la famille Stephenson, de Burlington, en Ontario

Deux officiers canadiens à côté de tombes canadiennes et britanniques récemment préparés dans le cimetière marin à l'extérieur de Vladivostok, 1 juin 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Opposition sur le front intérieur

Avant le départ pour la Russie du corps principal de la Force Expéditionnaire canadienne en Sibérie, le commandement militaire avertit le cabinet Borden:

« Que les dispositions en Sibérie manquent de coordination et de contrôle, que le système ferroviaire est dans un état de désorganisation sérieux, que parmi les Alliés il n'existe aucun accord général, que les Américains sont inactifs, que les Japonais, résolus de pénétrer le commerce sibérien, subventionnent des éléments rebelles ».

Ce fut un avertissement prémonitoire, anticipant l'échec de l'expédition canadienne en Sibérie. En février 1919, le gouvernement fut volte-face et ordonna l'évacuation de toutes unités canadiennes « sur les premiers navires disponibles ».1

La décision du Premier Ministre d'évacuer les troupes reflétait les conditions incertaines en Russie, mais aussi l'opposition du public canadien contre l'expédition. Comme l'opposition de la classe ouvrière contribua à la mutinerie à Victoria lorsque des socialistes canadiens exprimèrent de vives sympathies avec les Bolchéviks russes, ces tensions s'élargirent alors que le corps principal de la force navigua pour Vladivostok.

Les Conseils du Travail canadiens dans les quatre plus grandes villes - Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto et Montréal — s'opposèrent officiellement à l'expédition en Sibérie. Ils furent rejoints par les organisations d'agriculture, y compris les « United Farmers of Ontario » et le « Mount Hope Grain Growers Association » de Saskatchewan. Avec le Ministre de la Milice et de la Défense Sydney Mewburn de Hamilton, le journal pro-business Herald et Spectator se demanda si la décision de déployer des troupes canadiennes fut sage, déclarant que « les étrangers n'ont vraiment pas le droit de s'ingérer » dans les affaires internes russes.2 Ceci fait suite à d'autres critiques du journal de Toronto le Globe.

L'opposition contre l'expédition en Sibérie s'est étendu même à la Chambre des Communes d'Ottawa. Lors d'une réunion publique en mars 1919, Dr. Hermas Deslauriers, député de la circonscription montréalaise de Saint-Marie, déclara que l'expédition en Sibérie « doit être considéré comme un crime ». Un autre député du Québec, Edmund William Tobin, de Richmond-Wolfe, demanda au Ministre de la Défense: « Combien d'hommes furent enrôlés pour la Sibérie en vertu des dispositions de l'Acte de Service Militaire, 1917 » et demanda sous « quelle loi, décret ou autre autorité déclara que des hommes furent envoyés en Sibérie »?3

Comme la légalité du déploiement d'« hommes de l'ASM » en Russie fut scrutée, le Général Elmsley suspendu discrètement la peine des conscrits québécois « reconnu coupable de mutinerie à Victoria ».4

The Fallen

Collection de la famille Stephenson, Burlington, Ontario

Chapelains canadiens Harold McClausland et Jacques Oliviere, rejoints par d'autres officiers, à l'inauguration du monument commémoratif canadien au cimetière marin de Vladivostok, Russie, 1 juin 1919. Quatorze Canadiens furent enterrés sur ce site.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

En juin 1919, les Canadiens rentrèrent chez eux, à l'exception des dix-neuf soldats morts en Russie ou en mer, et cinq soldats canadiens qui désertèrent. Le commandement canadien dédia quatorze croix de bois et un monument de pierre au cimetière marin de Vladivostok sur la colline Monastirskaia, lors d'une cérémonie le 1er juin 1919 présidée par les Capitaines Harold McCausland et Jacques Olivier, chapelains Anglicans et Catholiques pour les forces canadiennes.

Trois autres soldats morts pendant le voyage à Vladivostok furent enterrés à la mer, et quatre soldats morts pendant le voyage de retour furent enterrés dans des cimetières de William Head, en Colombie-Britannique, Canada; à Ruthven, Ontario, Canada, et Canton; en Ohio, aux États-Unis.

Enterré au cimetière marin de Vladivostok

- Lieut. Alfred H. Thring, 260e Btn, s'est suicidé sur la route Gornostai, 18 mars 1919

- Pte. Walter Boston, 16e Ambulance de campagne, mort d'endocardite, le 16 avril 1919

- Rfn. William Edward Dodd, 260e Btn, mort de toxémie, le 5 avril 1919

- Rfn. Earl Gillespie, 260e Btn, mort de méningite cérébrospinale, le 14 mars 1919

- Rfn. David Higgins, 260th Btn, died of periocarditis, 6 March 1919

- Rfn. Romeo Lariviere, 259e Btn, mort de pneumonie, 11 mars 1919

- Rfn. James Florence Manion, 260e Btn, mort de pneumonie, le 22 février 1919

- Rfn. Joseph Emmett McDonald, 259e Btn, mort de pneumonie, le 28 février 1919

- Rfn. Roy Sothern, 260e Btn, mort de pneumonie, 4 mars 1919

- Pte. Edwin Howard Stephenson, 11e Hôpital Militaire, mort de la variole, le 23 mai 1919

- Gunner Frederic Eaton Ward, 20e Mitrailleur, mort de pneumonie et de scarlatine, 3 mars 1919

- A/QMS Ernest Worthington, Base de l'AC, mort de pneumonie, 6 mars 1919

- Sgt. John Shirley Murray Wynn, 16e Co. d'Ingénieurs, mort de froid, 14 janvier 1919

Enterré à la mer

- Pte. Edward Biddle, Garde de Base, mort de grippe à bord du SS Empress of Japan, 22 octobre 1918

- Rfn. Harold Leo Butler, 259e Btn, mort dans un accident à bord du SS Protésilas, 31 décembre 1918

- Rfn. Frank Joseph Kay, 259e Btn, mort dans un accident à bord du SS Teesta, 28 décembre 1918

Enterré au cimetière William Head,

Metchosin, Colombie-Britannique, Canada

- Pte. Richard Leonard Massey, No. 9 du Détachement de la COC, mort de la variole, le 30 mai 1919

- Rfn. Peter Roy McMillan, 259e Btn, mort de la variole, le 6 juin 1919

Enterré au cimetière Unis Ruthven,

Comté d'Essex, Ontario, Canada

- Pte. Wilfred Charles Lane, QG de la Force, mort de pneumonie à Hong Kong, 10 mars 1919

Enterré au cimetière de Lawn-Ouest,

Canton, Ohio, Etats-Unis

- L/Cpl. George H. Buckwalter, 20e Mitrailleur, mort de pneumonie à bord du SS Monteagle, le 25 avril 1919

PROFIL

Pte. Edwin Howard Stephenson, 1886-1919

Collection de la famille Stephenson, Burlington, Ontario

Edwin Stephenson, le jour où il fut ordonné comme prêtre anglican, Desboro, en Ontario, le 26 mai 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Edwin Howard Stephenson est né en avril 1886 à Tillsonburg, en Ontario. Anglican pratiquant, il travailla dans le village de Desboro pendant les premières années de la Première Guerre Mondiale. Stephenson fut ordonné prêtre le 21 mai 1918. Le lendemain, il s'enrôla dans l'Armée canadienne en tant que soldat non-combattant: un infirmier dans le Corps Médical de l'Armée canadienne.

Lors de la formation de la Force Expéditionnaire canadienne (en Sibérie) en août 1918, le Sdt. Stephenson était attaché au 11e Hôpital Militaire. Il se rendit à Vladivostok avec le parti d'avance à bord l'Empress of Asia en octobre 1918. En décembre 1918, Stephenson voyaga « à l'intérieur du pays » — avec le partie d'avance de 55 canadiens à Omsk. Il fut l'un des rares canadien à atteindre l'intérieur sibérien.

Collection de la famille Stephenson, Burlington, Ontario

Edwin Stephenson, Soldat de l'Armée canadienne, c. l'automne 1918.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Stephenson compila un intéressant album de photos le long du Chemin de Fer Transsibérien, montrant les paysages, les villages et les gens le long de la piste, ainsi que des ponts détruits par les partisans. Il passa l'hiver de 1918-19 dans la capitale de Koltchak, en attendant le corps principal de la force canadienne (qui n'arriva jamais). En avril, Stephenson et le parti canadien évacuèrent Omsk.

Collection de la famille Stephenson, Burlington, Ontario

Edwin Stephenson avec un groupe de garçons au marché chinois de Vladivostok, avant sa mort de la variole.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Edwin Stephenson retourna à Vladivostok lorsque le gouvernement canadien se bousculait pour trouver les navires capables de ramener les 4200 soldats au Canada. En attendant leur évacuation, il contracta la petite vérole et mourut à l'hôpital « Second River » le 24 mai 1919.

Stephenson fut enterré à côtés des treize autres Canadiens et quatorze soldats britanniques dans le cimetière marin de Vladivostok, près de la parcelle pour les soldats tombés tchécoslovaques, français et japonais. Sa tombe fut marquée d'une croix de bois blanche et commémoré par le commandement canadien, le 1er juin 1919.

Dans les années 1990, suivant la fin de la Guerre froide, Vladivostok ouvra ses portes aux étrangers, et une pierre tombale en granit fut érigé par des Marines canadiennes. Aucun membre de sa famille eu l'occasion de visiter Edwin Stephenson à sa place de repos. J'aimerai remercier Gwen Stephenson, de Burlington, en Ontario, pour avoir eu la gentillesse de partagé le journal et les photos de son oncle Edwin.

Collection de la famille Stephenson, Burlington, Ontario

Tombe d'Edwin Stephenson, cimetière marin de Vladivostok, c. mai 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Photographie par Benjamin Isitt

Tombe d'Edwin Stephenson, cimetière marin de Vladivostok, 2008.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Conséquences

Histoire visuelle du Canada

Annonce anti-OBU publié pendant la grève générale de Winnipeg. Les travailleurs Canadiens furent adeptes à la OBU, et initièrent des grèves de solidarité de Victoria à Amherst, en Nouvelle-Écosse, c. mai 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

S'adressant au Parlement le 10 juin 1919, le Dr. Henri Sévérin Béland, député de Beauce, déclara: « Cette expédition fut une erreur politique, une erreur militaire, et une extravagance sans motif ».5 Béland, un héros de guerre libérés d'un camp de prisonniers de guerre en Allemagne, exprimait une opinion largement répandue au Canada. Il formula ses observations lors de la crise industrielle la plus importante de l'histoire du Canada.

Cette vague d'agitation industrielle s'étendue de la côte ouest à la Nouvelle-Écosse, où les travailleurs de la « Canadian Car and Foundry Company » et d'autres usines à Amherst déclarèrent une grève pour la « One Big Union ». Général Elmsley et le SS Monteagle ratteignirent Vancouver, en pleine grève, le 22 juin avec les restes de la Force Expéditionnaire canadienne en Sibérie. Environ cent cinquante gendarmes de l'Escadron B de la RGCN-O débarquèrent sous une pluie de briques et pierres venant de débardeurs et furent promptement donné l'ordre de service de grève.

Histoire visuelle du Canada

Agents de la RGCN-O chargeant la rue Main à Winnipeg à cheval et ouvrant le feu. Rejoint par des soldats canadiens réguliers en kaki, les autorités tirèrent sur 50 grévistes et en tuèrent deux, sapant la force de la grève générale de Winnipeg. « Samedi sanglant », 21 juin 1919. Le corps de l'un des deux hommes tués, Mike Sokolowski, est sur le trottoir.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

« Il semble y avoir aucune raison précise pour [la] grève, sauf [le désir] d'agents étrangers, apparemment dans le contrôle des syndicats, de provoquer une guerre de classe à travers l'Amérique et de prendre le contrôle de la production », observa le Lieutenant-Colonel Geoffrey McDonnell.6

Histoire visuelle du Canada

L'Armée canadienne occupa Winnipeg, la troisième plus grande ville du Canada, et mit fin à l'un des défis d'ouvriers contre leurs employeurs et l'État les plus audaces de l'histoire canadienne. 21 June 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

En Sibérie et en Extrême-Orient russe, l'effort de guerre Alliés-Blanc s'effondra totalement. L'Armée Rouge saisi Omsk en novembre et les dernières troupes britanniques furent évacuées. En janvier 1920, les partisans à Vladivostok renversèrent le gouverneur militaire local de Koltchak, Général Pavel Ivanov-Rinov, dans un coup d'État sans violence. À Irkoutsk, la Légion mutinée tchécoslovaque remis Koltchak aux autorités locales Rouge, qui exécutèrent l'ancien dictateur Blanc.

Les Américains se retirèrent de Vladivostok en avril 1920, suivie par les tchécoslovaques en mai, qui naviguèrent à l'autre côté du monde pour leur nouvelle patrie. En route, ils passèrent par Vancouver, armés, avant de monter dans des trains du Chemins de Fer du Canadien Pacifique pour l'est.

La lutte pour le pouvoir continua pour deux ans dans l'Extrême-Orient russe, comme une série d'administrations Blanches et Rouges se suivirent, aux côtés d'une République anormale de l'Extrême-Orient. Enfin, le 25 octobre 1922, les dernières unités japonaises évacuèrent Vladivostok lorsque des colonnes de troupes de l'Armée Rouge entrèrent dans la ville. L'Union Soviétique s'étendit des océans Pacifique et Arctique aux mers Caspienne, Noire et Baltique — détenteurs du pouvoir pour les sept prochaines décennies.

Dans les années qui suivirent l'évacuation canadienne de Vladivostok, le bois des vieilles croix sur la colline Monastirskaia pourrirent à cause du temps et de la négligence, comme peur Rouge et Guerres Froides coupèrent cette ville du reste du monde. Après la Seconde Guerre Mondiale, les autorités soviétiques déclarèrent Vladivostok une ville « fermée », refusant accès aux étrangers pour mieux garder leur flotte de sous-marins nucléaires.

Photographie par Benjamin Isitt

Monument canadien au cimetière marin de Vladivostok, 2008. Quatorze Canadiens furent enterrés sur cette colline tranquille près de la ville, à coté des tombes des troupes britanniques, françaises, tchèquoslovakes et japonaises.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Dans les années 1990, lorsque l'Union Soviétique fut dissoute, le monde occidental chercha à restaurer son influence dans l'Extrême-Orient russe, un parti canadien à bord du HMCS Protector se rendu à Vladivostok, et travailla pendant trois semaines pour restaurer les tombes canadiennes et britanniques sur la colline Monastirskaia. Le Comité Parlementaire canadien des Affaires Étrangères avait reçu la preuve que:

« Il y a des tombes canadiennes à Vladivostok dans de terrible conditions. Certaines pierres tombales furent renversées et volées. Du graffiti fut peint sur quelques-unes de ces pierres. Il me semble être dommage qu'ils sont oubliées ».7

Les soldats canadiens tombés ne furent pas les seules victimes de ce moment controversée dans le passé de ce pays. Dans les mots d'une thèse de troisième cycle écrite il y a cinquante ans, l'expédition en Sibérie devenu « qu'un souvenir pour d'anciens soldats ».8 Le résultat des pressions géopolitiques de la Première Guerre Mondiale et la Révolution russe, l'histoire de expédition canadienne en Sibérie fut largement oublié. C'est le devoir de nouvelles générations de se rappeler de cette histoire contestée.

Pour l'histoire complète, lire le livre

From Victoria to Vladivostok: Canada's Siberian Expedition

Notes

- 1 Lash à Mewburn, 3 décembre 1918, BAC, RG 24, sér. C-1-A, vol. 2557, dossier HQC-2514 (vol. 1); « Inquiry of the Ministry by Mr. Demers, No. 58, Orders of the Day No. 23 », 27 mars 1919, BAC, RG 24, sér. C-1-A, vol. 1993, dossier 762-11-24, « Queries Relating to CEF (Siberia) ».

- 2 Gordon Grey, « Canada and the Siberian Expedition », The Nation (New York), 1 février 1919, 162-63; « Canadians in Russia », Hamilton Herald, 13 décembre 1918

- 3 Extrait du discours du Dr. Hermas Deslauriers, Division de St-Mary, Montréal, 11 mars 1919, BAC, RG 24, sér. C-1-A, vol. 2557, dossier HQC-2514 (vol. 2), « Situation in Russia – Allied Intervention in Russia », Ordre de la Chambre des Communes, le 7 avril 1919, BAC, RG 24, sér. C-1-A, vol. 1992, dossier de l'AC-762-11-27, « Inquiry House of Commons by Mr. Tobin »; Canada, Compte rendu des débats de la Chambre des Communes, le 1er avril 1919.

- 4 Defensor à Elmsley, le 1er avril 1919, Bickford au quartier général de la FECS, 5 avril 1919, Elmsley à Defensor, le 10 avril 1919 (tous dans la BAC, RG 9, Ser. III-A-3, vol. 373, dossier A3, Force SEF HQ MSA); Swift au quartier général de Brigade, le 8 avril 1919, Barclay à Elmsley, 11 avril 1918, Barclay à Elmsley, 12 avril 1919, suspension de peine, 14 avril 1919 (tous en BAC, RG 9,Ser. III-A-3, vol. 371, dossier A3, SEF QG de la Force 23).

- 5 Canada, Compte rendu des débats de la Chambre des communes, 10 Juin 1919, p. 3298.

- 6 Les grèves de solidarité du printemps 1919 sont examinés dans Gregory S. Kealey, « 1919: the Canadian Labour Revolt », Labour/Le Travail 13 (Spring 1984): 11-44; Alan Phillips, The Living Legend: The Story of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Toronto and Boston: Little, Brown, 1954), 86; Rapport du Major G.F. Worsley sur l'Escadron B de la RGCN-O, 11 octobre 1919, BAC, RG 18, Collection de la GRC, vol. 3179, dossier G 989-3 (vol. 2); Télégramme de l'« Empress of Russia », s.d.[c. juin 1919], Hoover Institution Archives, Geoffrey McDonnell Collection, acc. XX233-10 A-V.

- 7 Canada, Ministère des Affaires Étrangères, « Evidence », 30 mai 1995, DEFA bloc de 25 101, http://www.parl.gc.ca/35/Archives/committees351/defa/evidence/25_95-05-30/defa25_blk101.html (consulté le 14 juillet 2008).

- 8 Stuart Beattie, « Canadian Intervention in Russia, 1918-1919 ». (MA thesis, McGill University, 1957), 409.

Sauter à

Эвакуация

Канадцы эвакуировались из Владивостока на 4 кораблях в промежутках между маем и июнем 1919г. Перед отплытием на Морском кладбище был заложен мемориальный камень в память о гибели 14 канадцев во Владивостоке. Среди них был рядовой Эдвин Стефенсон, англиканский священник, служивший врачом канадского отряда в Омске. По возвращению из Сибири во Владивосток Стефенсон заболел оспой и умер в госпитале на Второй речке за неделю до отплытия его корабля в Канаду. Пятеро других солдат погибли в море.

Коллекция Роберта Макная, г. Катрин, Канада

Канадские солдаты, идущие на борт корабля «Императрица России» 19 мая 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Уже в Британской Колумбии на карантине вблизи г. Виктория умерло еще два солдата. Вернувшись на родину, канадцы разделились на два социальных класса, активно участвующих в забастовках от Виктории до Виннипега. История о Сибирской экспедиции, как о первом вторжение Канадцев на Дальний Восток была практически забыта.

Коллекция семьи Стефенсона, г. Бурлингтон, Канада

Два канадских офицера стоят у канадских и британских захоронений на Морском кладбище в пригороде Владивостока, 1 июня 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Оппозиция на внутреннем фронте

Перед отправкой основных военных сил в Сибирь, военное командование предупредило кабинет Бодена:

«Отсутствие координации и контроля в Сибири подрывают все ранее установленные договоренности, железная дорога серьезно дезорганизована, среди союзников нет общего согласия, поскольку американцы не активны, а японцы слишком заинтересованы в экономическом внедрении в регион, используя для этих целей белогвардейцев».

Это предупреждение оказалось пророческим, предвидя провал Канадской военной экспедиции в Сибирь. В феврале 1919г. правительство неохотно изменило курс на эвакуацию всех войск в Канаду «на первых доступных судах».1

Решение Премьер-министра об эвакуации было обусловлено сложными условиями в России, а также ростом общественного мнения против интервенции в Канаде. Рабочий класс, заявивший о себе во время Мятежа в Виктории, продолжал симпатизировать русским большевикам.

Рабочий совет из четырех крупнейших городов Канады – Ванкувер, Виннипег, Торонто и Монреаль также выступил против Канадской экспедиции. К ним присоединились и фермерские организации, среди которых Объединенные фермеры Онтарио и ассоциации Маунт Хоуп в Саскачеване. Министр милиции и обороны Сидни Мьюберн давал интервью бизнес газетам Геральд и Спектетор где на вопрос о том, в чем заключалась мудрость в отправке войск, он ответил: «посторонние не имеют права вмешиваться» во внутренние дела России.2 Это заявление последовало после критики в газете Globe (Торонто).

Противники экспедиции в Сибирь стали также появляться в Палате Общин в Оттаве. На публичном слушании в марте 1919г. доктор Гермэс Деслауриер из Монреаля заявил, что Сибирская экспедиция «должна рассматриваться как преступление». Другой выступающий из Квебека Эдмунд Уильям Тобин спросил министра обороны, — «сколько мужчин принятых в армию по акту обязательной военной службы 1917г. были отправлены в Сибирь» и «что за закон, приказ или Совет отправил ребят в Сибирь?». 3

Поскольку эти вопросы возникли по поводу законности отправки этих мужчин для службы в Россию, генерал Элмслей отменил решение военного суда по призывникам из Квебека «участвующих в мятеже».4

Падение

Коллекция семьи Стефенсона, Онтарио

Канадские священники Герольд МакКлаусланд и Жак Оливиер вместе с канадскими офицерами на открытие канадского мемориала на Морском кладбище во Владивостоке 1 июня 1919г., где захоронено 14 канадцев.

Больше фотографий в архиве

В июне 1919 г. канадцы уже были дома, за исключением 19 солдат, что погибли во Владивостоке или в море, а также пяти солдат, дезертирующих в России. Канадское командование посвятило 14 деревянных крестов и каменный монумент всем погибшим канадцем на Морском кладбище. Священник англиканской церкви Герольд МакКлаусланд и католический пастор Жак Оливиер провели службу.

Трое солдат, умерших по дороге во Владивосток были похоронены в море. Четверо других, умерших на пути домой в Канаду захоронены на кладбищах в Уильям Хед в Британской Колумбии и в провинции Онтарио в Канаде, а также в штате Огайо в США.

Список похороненных канадцев на Морском кладбище Владивостока

- Лейтинант Альфред Тринг, 260 батальон, самоубийство около бухты на Горностае, 18 марта 1919г.

- пехотинец Вальтер Бостон, 16 полевой госпиталь, умер от эндокардита, 16 апреля 1919г.

- стрелок Уильям Додд, 260 батальон, умер от таксинемии, 5 апреля 1919г.

- стрелок Ирл Джилиспи, 260 батальон, умер от менингита, 14 марта 1919г.

- стрелок Дэвид Хиггинс, 260 батальон, умер от перикардита, 6 марта 1919 г.

- стрелок Ромео Лиривиер, 259 батальон, умер от пневмонии, 22 февраля 1919г.

- стрелок Джеймс Флоренс МАнион, 260 батальон, умер от пневмонии, 22 февраля 1919г.

- стрелок Джозеф Эммет МакДональд, 259 батальон, умер от пневмонии, 28 февраля 1919г.

- стрелок Рой Созерн, 260 батальон, умет от пневмонии, 4 марта 1919г.

- Рядовой Эдвин Говард Стефенсон, 11th Stationary Hospital, died of small pox, 23 мая 1919г.

- Фредерик Итон Вард, 20 стрелковая компания, умер от пневмонии и красной лихорадки, 3 марта 1919г.

- Эрнест Уортингтон, военный штаб, умер от пневмонии, 6 марта 1919г.

- сержант Джон Мурэй Уинн, 16 полевая компания, умер от переохлаждения, 14 января 1919г.

Канадцы, захороненные в море

- пехотинец Эдвард Байддл, охранник, умер от гриппа на борту судна «Императрица Японии», 22 октября 1918г.

- стрелок Гарольд Лео Батлер, 259 батальон, умер от несчастного случая на судне «Протесилаус», 31 декабря 1918г.

- стрелок Фрэнк Джозеф Кай, 259 батальон, умер от несчастного случая на борту судна «Тееста», 28 декабря 1918г.

Канадские захоронения на кладбище Уилльям Хэд,

г. Метчозим, Британская Колумбия, Канада

- пехотинец Ричард Леонард Массей, No. 9 Detachment COC, умер от оспы, 30 мая 1919г.

- стрелок Рой МакМиллан, 259 батальон, умер от оспы, 6 июня 1919г.

Захоронение на общем кладбище Русвен,

в Эссексе, Онтарио, Канада

- пехотинец Вилфред Чарльз Лан, канадский военный штаб, умер от пневмонии в Гонконге, 10 марта 1919г.

Захоронение на кладбище Вест Лавн,

г. Кантон, штат Огайо, США

- капрал Джордж Баквальтер, 20 стрелковая кампания, умер от пневмонии на борту корабля «Монтегл», 25 апреля 1919г.

Очерк

Рядовой Эдвин Говард Стефенсон, 1886-1919

Коллекция семьи Стефенсона, г. Барлингтон, Канада

Эдвин Стефенсон в день, когда он получил титул священника англиканской церкви, г. Десборо, Онтарио, 26 мая 1918г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Эдвин Говард Стефенсон родился в апреле 1886г. в г. Тилсонбарг, Онтарио. Он ушел в духовенство Англиканской церкви, работал в деревни Десборо до первых лет Первой мировой войны. Стефенсон был призван на фронт как священник 21 мая 1918г. На следующий день он был завербован в Канадскую армию, как не конбанат — а как медик в Канадском военном медицинском корпусе.

Когда происходило формирование Канадских экспедиционных сил в Сибири в августе 1918г. Стефенсон был зачислен за 11 госпиталем. Он отплыл во Владивосток с первыми отрядами на корабле «Императрица Азии» в октябре 1918г., он был одним из 55 канадцев, что посетили с миссией Омск.

Коллекция семьи Стефенсона, г. Барлингтон, Канада

Рядовой Эдвин Стефенсон, Канадский военный медицинский корпус, осень 1918г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Стефенсон собрал удивительный альбом фотографий, запечатлевший жизнь вдоль Транссибирской железной дороги: бытовую жизнь Сибири, деревни и людей вдоль рельсов, взорванные партизанами мосты. Он провел зиму 1918-1919г. в столице колчаковского правительства в ожидание основных канадских сил в Омске (которые так и не прибыли). В апреле он уехал из Омска с канадским военным корпусом.

Коллекция семьи Стефенсона, г. Барлингтон, Канада

Рядовой Эдвин Стефенсон с мальчиками на китайском рынке Владивостока, незадолго до своей смерти от оспы.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Стефенсон вернулся во Владивосток как раз в тот момент, когда канадское правительство приступило искать суда для эвакуации 4200 своих солдат и офицеров домой. В ожидание своего судна от заразился оспой и умер в госпитале на Второй речке 24 мая 1919г.

Стефенсон был похоронен среди тринадцати других канадцев и четырнадцати британских военных на Морском кладбище, где также нашли свой последний покой чехословаки, французы и японцы. Его могила была обозначена ровным деревянным крестом с надписью, сделанной 1 июня 1919г.

В 1990х, когда холодная война закончилась и Владивосток вновь стал открытым городом для иностранцев, на Морском кладбище был отреставрирован Канадский мемориальный комплекс, появились гранитные надгробия (данное мероприятие проводилось в 2002г. при участие Почетного консульства Канады во Владивостоке и Канадских военно-морских сил, прим. переводчика). Никто из членов семьи Стефенсона не имел возможности посетить его могилу ни до, ни после этого события.

Коллекция семьи Стефенсона, г. Барлингтон, Канада

Могила Эдвин Стефенсона, Морское кладбище, Владивосток, май 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Фотография Бэнджамина Айситта

Могила Эдвин Стефенсона, Морское кладбище, Владивосток, 2008г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Послесловие

Канадская визуальная история, архив

Anti-OBU advertisement, published in the midst of the Winnipeg General Strike as the OBU sunk roots among Canadian workers and sympathy strikes erupted from Victoria to Amherst, Nova Scotia. c. May 1919.

Больше фотографий в архиве

На слушаниях в Парламенте 10 июня 1919г. Др. Генри Беланд, член парламента от Беац, заявил: «Канадская экспедиция в Сибирь была политической и военной ошибкой, совершенно ничем не обоснованным шагом».5 Беланд будучи военным героем, прошедшим немецкий лагерь военнопленных, дал наиболее лучшее описание ситуации в Канаде. В своих замечаниях он наиболее полно описал промышленный кризис в Канаде той поры.

Волна рабочих волнений прошла от западного побережья Канады до Новой Шотландии, где рабочие канадского машиностроения и литейщики создали один большой союз. Генерал Элмслей на корабле «Монтегл» пришвартовался в Ванкувере 22 июня. Сто пятидесяти полицейским из Канадской северо-западной горной полиции сразу при сходе на берег пришлось расчищать причал от груды битых кирпичей и камней, насыпанных на пирс протестующими рабочими порта.

Канадская визуальная история, архив

Офицеры Королевской северо-западной горной полиции на лошадях открывают огонь по протестующим в Виннипеге. В ходе этой стачки было ранено 50 человек, двое убито. 21июня 1919г. вошел в историю как «Кровавая суббота». Тело одного из убитых Майка Соколовского можно разглядеть на обочине.

Больше фотографий в архиве

По мнению лейтенант-полковника МакДонелла данные беспорядки «могли только быть вызваны международными агентами, что желают наложить свой контроль на промышленные союзы и все производство Канады путем провоцирования классовой борьбы по всей Америке».6

Канадская визуальная история, архив

Канадские военный занимают третий по величине город в стране Виннипег, положив конец одному из самых крупных в истории Канады восстанию рабочих. Подавление стачки 21 июня 1919г. получило название «Кровавая суббота».

Больше фотографий в архиве

В Сибири и на Дальнем Востоке планы союзников по Антанте и Белой русской армии претерпели крах. Красная армия заняла Омск в ноябре, с отбытием последних британских военных сил. В январе 1920г. партизаны Владивостока свергли в результате бескровного переворота местного военного губернатора Колчака генерала Павла Иванова-Ринова. В Иркутске мятежный чехословацкий легион сдал Колчака местным Красным властям, которые приговорили бывшего Белого диктатора к расстрелу.

Американцы ушли из Владивостока в апреле 1920г., в мае за ними последовали чехословаки. Их путь до родины обернулся кругосветным плаванием. По пути к дому тысячи вооруженных чехов прошли по Ванкуверу, сели в поезда Тихоокеанской железной дороги и отправились на восточное побережье Канады для отплытия в Европу.

Последующие два года характеризовались постоянной сменой властью Красных и Белых на российском Дальнем Востоке, а также созданием своеобразной Дальневосточной республикой. В итоге 25 октября 1922г. последние японские военные части покинули Владивосток, в тот же день Красная армия вошла в город. Так закончилась гражданская война, Советский Союз растянулся от берегов Тихого океана до Балтийского моря, удерживая власть семь десятилетий.

Спустя годы после канадской эвакуации из Владивостока, деревянные кресты на Морском кладбище обветшали от времени и скрылись под землей, а холодные войны и страхи «красной угрозы» отдалили город от остального мира. После Второй мировой войны советские власти превратили Владивосток в «закрытый город» для иностранцев с целью обеспечения секретности своего атомного подводного флота.

Фотография Бэнджамина Айситта

Канадский памятник на Морском кладбище во Владивостоке, 2008г. Четырнадцать канадцев похоронены здесь, на склоне тихой сопки поблизости с могилами британских, французских, чехословацких и японских солдат.

Больше фотографий смотрите в архиве

В 1990-х гг., когда Советский Союз рухнул, Запад приступил к возрождению своего влияния на российском Дальнем Востоке. Команда канадского военного корабля «Протектор» работала три недели над восстановлением канадских и британских захоронений на сопке Монастырская (Морское кладбище). Канадский парламентский комитет по международным делам выслушал нелицеприятный отчет:

«Забытые канадские могилы во Владивостоке находятся в ужасном состоянии. Каменные надгробия были либо похищены, либо опрокинуты. Надписи различимы лишь на некоторых плитах. Должно быть стыдно, что мы о них забыли».7

Погибшие канадские солдаты не только являются частью противоречивого момента в истории страны. В одной дипломной работе, написанной пятьдесят лет назад, сказано, что Сибирская экспедиция стала «лишь памятью для старых солдат».8 Рожденная в хаотичные годы Первой мировой войны и русской революции, история о Канадской сибирской экспедиции была забыта. Теперь для нового поколения есть задача – помнить столь противоречивую страницу истории.

Полную историю читайте в книге

Из Виктории во Владивосток: Канадская сибирская экспедиция

Примечания

- 1 Lash to Mewburn, 3 December 1918, LAC, RG 24, ser. C-1-A, vol. 2557, file HQC-2514 (vol. 1); “Inquiry of the Ministry by Mr. Demers, No. 58, Orders of the Day No. 23,” 27 March 1919, LAC, RG 24, ser. C-1-a, vol. 1993, file 762-11-24, “Queries Relating to CEF (Siberia).”

- 2 Gordon Grey, “Canada and the Siberian Expedition,” The Nation (New York), 1 February 1919, 162-63; “Canadians in Russia,” Hamilton Herald, 13 December 1918

- 3 “Extract of Speech of Dr. Hermas Deslauriers, St-Mary Division, Montreal, 11 March 1919, LAC, RG 24, ser. C-1-A, vol. 2557, file HQC-2514 (vol. 2), “Situation in Russia – Allied Intervention in Russia”; Order of the House of Commons, 7 April 1919, LAC, RG 24, ser. C-1-a, vol. 1992, file HQ-762-11-27, “Inquiry House of Commons by Mr. Tobin.” See also Canada, Report of Debates of the House of Commons, 1 April 1919.

- 4 Defensor to Elmsley, 1 April 1919, Bickford to Headquarters CEF(S), 5 April 1919, Elmsley to Defensor, 10 April 1919 (all in LAC, RG 9, ser. III-A-3, vol. 373, file A3, SEF Force HQ MSA); Swift to Brigade Headquarters, 8 April 1919, Barclay to Elmsley, 11 April 1918, Barclay to Elmsley, 12 April 1919, “Suspension of Sentence,” 14 April 1919 (all in LAC, RG 9, ser. III-A-3, vol. 371, file A3, SEF Force HQ 23.

- 5 Canada, Report of Debates of the House of Commons, 10 June 1919, p. 3298.

- 6 The sympathetic strikes of spring 1919 are examined in Gregory S. Kealey, “1919: The Canadian Labour Revolt,” Labour/Le Travail, 13 (Spring 1984): 11-44; Alan Phillips, The Living Legend: The Story of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Toronto and Boston: Little, Brown, 1954), 86; Major G.F. Worsley Report on “B” Squadron RNWMP, 11 October 1919, LAC, RG 18, RCMP Collection, vol. 3179, file G 989-3 (vol. 2); Telegram “Empress of Russia,” n.d. [c. June 1919], Hoover Institution Archives, Geoffrey McDonnell Collection, acc. XX233-10 A-V.

- 7 Canada, Department of Foreign Affairs, “Evidence,” 30 May 1995, DEFA 25 Block 101, http://www.parl.gc.ca/35/Archives/committees351/defa/evidence/25_95-05-30/defa25_blk101.html (viewed 14 July 2008).

- 8 Steuart Beattie, “Canadian Intervention in Russia, 1918-1919” (MA thesis, McGill University, 1957), 409.

Перейти к

Research Questions

- Why did the government of Canada decide to evacuate the troops before the main body had even reached Vladivostok?

- What is the legacy of Canada's Siberian Expedition?

Key Themes

- • Canada's evacuation of Vladivostok

- • Social unrest on the Homefront and the 1919 labour revolt

- • Commemorating the Fallen

- • Contested memories of the First World War

Questions de Recherche

- Pourquoi est-ce que le gouvernement canadien décida d'évacuer les troupes avant que le corps principal eu atteint Vladivostok?

- Quel fut l'héritage de l'expédition canadienne en Sibérie?

Principaux thèmes

- • L'évacuation canadienne de Vladivostok

- • L'agitation sociale sur le front domestique et de la révolte ouvrière de 1919

- • Commémoration des morts

- • Contestation des souvenirs de la Première Guerre Mondiale

Исследуемый вопрос

- Почему правительство Канады решило вывести войска из России еще до того, как основные военные силы пришвартовались во Владивостоке?

- Какое наследие после себя оставила Канадская сибирская экспедиция?

Ключевые темы

- • Эвакуация канадцев из Владивостока

- • Общественные беспорядки и рабочие забастовки в Канаде в 1919г.

- • Память по погибшим в Сибири

- • Спорные воспоминания о Первой мировой войне

Primary Documents

- "Another Mother’s Protest," Globe (Toronto), 31 December 1918 (coming soon)

- Globe editorial on the Siberian Expedition

- Letters from family members (coming soon)

- Henri Beland speech in Parliament, March 1919 (coming soon)

- Alberta Federation of Labor resolution for General Strike, January 1919

- Troop movements to and from Vladivostok

- Lt. McDonnell telegram on Vancouver General Strike, June 1919 (coming soon)

- "Would Set Up a Soviet," Daily Colonist (Victoria), 21 June 1919 (coming soon)

- Charles Hertzberg diary on preparation of Canadian plot (coming soon)

- Imperial War Graves Commission, Cemeteries and Memorials: Asia I-50 (London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1931) (coming soon)

- Department of Militia and Defence Historical Section, correspodence on Siberian Expedition, March 1928

- Parliament of Canada Records on Cemetery, 1998 (coming soon)

Multimedia:

- Eric Elkington interview

- CBC radio documentary "Canada and the Siberian Intervention" (1970)

- Gwen Stephenson interview (coming soon)

- Video from Vladivostok Marine Cemetery (March 2008)

- Video from Vladivostok Marine Cemetery (October 2009)

- Video from William Head war graves

Photos from Digital Archive:

Documents primaire

- « Another Mother’s Protest”, Globe (Toronto), 31 décembre 1918

- Éditorial du Globe sur l'expédition en Sibérie

- Les lettres des membres de familles militaires

- Discours d'Henri Béland au Parlement, mars 1919

- Résolution de l'« Alberta Federation of Labor » sur la grève générale, janvier 1919

- Les mouvements de troupes en provenance et à Vladivostok

- Le télégramme du Lieutenant McDonnell sur la grève général de Vancouver, juin 1919

- « Would Set Up a Soviet », Daily Colonist (Victoria), 21 juin 1919

- Journal de Charles Hertzberg sur la préparation d'une conspiration au Canada

- Commission Impériale de Tombe de Guerre, Cimetières et monuments: l'Asie I-50 (Londres: Stationary Office de Sa Majesté, 1931)

- Section historique du Ministère de la Milice et de la Défense, le correspondance de l'expédition en Sibérie, mars 1928

- Documents du Parlement du Canada sur cimetières, 1998

Multimédia

- Interview d'Eric Elkington

- Documentaire radio de la CBC « Canada and the Siberian intervention » (1970)

- Interview de Gwen Stephenson

- Vidéo du cimetière marin de Vladivostok (mars 2008)

- Vidéo du cimetière marin de Vladivostok (octobre 2009)

- Vidéo des sépultures de guerre de William Head

Photos de l'Archive Numérique

Первичные документы

- протест «чужой матери» статья в газете «Глоуб» (Торонто) 31 декабря 1918г.

- передовая статья в «Глоуб» о Сибирской экспедиции

- Письма членов семьи

- Речь Хенри Беленда в Парламенте, март 1919г.

- Резолюция Рабочей федерации Альберты о всеобщей забастовке, январь 1919г.

- Отправка войск во Владивосток и из Владивостока на родину

- Телеграмма лейтенанта Макдоннелла участникам «главной стачки» в Ванкувере в июне 1919г.

- «Налаживание отношений с Советами» газета Дэйли Колонист (г. Виктория) 21 июня 1919г.

- Дневник Чарльза Хецберга, где идет речь о подготовке канадского участка на Морском кладбище Владивостока

- Императорская комиссия по воинским захоронениям и памятниками в Азиатском регионе. Asia I-50 (London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1931)

- Отдел милиции и обороны. Исторический раздел. Переписка о Сибирской экспедиции. Март 1928г.

- Отчет парламента Канады о Морском кладбище во Владивостоке, 1998 г.

Мультимедия

- Интервью с Эриком Элкингтоном

- Документальный радиорепортаж «Канада и интервенция в Сибирь» 1970г.

- Интервью с Гвеном Стефенсоном

- Видео запись с Морского кладбища, г. Владивосток (марта 2008г.)

- Видео запись с Морского кладбища, г. Владивосток (Октябрь 2009г.)

- Видео запись с военного кладбища Уильям Хэд

English

English Français

Français Русский

Русский