Life in Vladivostok

Most of the 4,200 Canadians never left Vladivostok, a port city that a Canadian mounted police officer described as “about 90 percent Bolshevik.” Lacking authorization to proceed “Up Country” to the Siberian interior, the Canadian troops “did nothing,” trying to keep busy with guard duty, routine parades, and recreational pursuits — hockey, soccer, and boxing matches, vaudeville shows and two brigade newspapers, Russian-language lessons, hikes on the seashore and forests, and taking leave from the barracks in vice-filled "Vladi" (as they called the city).

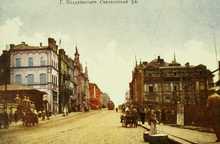

Sidney Rodger Collection, Beamsville, Ontario

Postcard of the street scene on Svetlanskaya Street, Vladivostok, c. 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

The recollections and photographs of soldiers such as Eric Elkington offer rich insight into the social life of the military force and relations with Vladivostok’s civilian population, including a large number of ethnically Chinese and Korean residents and refugees from the Siberian interior. Soldiers’ recollections also reveal the dark side of military interventions — violence, human suffering, and the sex trade.

PROFILE

Capt. Eric Elkington and the Winter of 1918-1919

"The setting of the town of Vladivostok was indeed beautiful seen from the boat in the early morning. The city follows the half moon curve of the bay and seems to be far greater in length than in breadth. Behind the town were low snow covered hills above which the sun was just rising. We could make out several substantial and well built looking buildings one of which was evidently a Greek church with a large golden dome flashing in the early morning sun."[5]

This is how medical officer Capt. Eric Elkington described the arrival of the Canadian troopship Protesilaus into Vladivostok’s Golden Horn Bay on the morning of January 15th, 1919.

Library and Archives Canada, Raymond Gibson Collection, 1977-157, C-91765

Canadian troopship at Egersheld wharf, Vladivostok, 1919. A few kilometres south of the city centre, near the mouth of Golden Horn Bay, Egersheld was the main docking facility and the site of the Canadian ordnance and supply sheds.

View more photos like this in the archive

Show me what it looks like today

Canada’s Advance Party had reached Vladivostok at the end of October 1918, with commanding officer Major-General James H. Elmsley requisitioning the majestic Pushkinsky Theatre for his force headquarters — prompting protests by Vladivostok businesspeople.

Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection, 19980027-020 #10

Pushkinsky Theatre, Canadian force headquarters from 27 October 1918 to 5 June 1919. The eviction of the Vladivostok Cultural-Enlightenment Society, which owned the stately building, fueled resentment among Vladivostok businessmen, who organized a large protest meeting. The Canadians refused to vacate the premises.

View more photos like this in the archive

Show me what it looks like today

Elmsley's officers and enlisted men began preparing for the arrival of the main body of the Canadian force, organizing barrack space at Second River and Gornostai Bay, and opening a White Russian officers’ training school on Russian Island at the mouth of Golden Horn Bay (Zolotoi Rog).

Five Canadian trade commissioners also arrived in Vladivostok, establishing an office on Svetlanskaya Street for the Canadian-Siberian Economic Commission, which sought to strengthen Canada's commercial interests in Siberia and the Russian Far East. These aspirations came to nothing, reflecting the chaotic economic conditions of the civil war. But the Royal Bank of Canada briefly operated a branch in Vladivostok in the winter of 1918-19.

Library and Archives Canada, Raymond Gibson Collection, 1977-157, C-91757

Canadian barracks at Vtoraya Ryechka (Second River), north of Vladivostok, 1919. The RNWMP's B Squadron was quartered here, as well as White Russian civilians displaced by the revolution.

View more photos like this in the archive

Show me what it looks like today

With the arrival of the SS Teesta and SS Protesilaus in January 1919, the Canadian force at Vladivostok numbered nearly 4,000 men — and one woman, Nursing Matron Grace Eldrida Potter.

Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection, 2005110-009 p3

A rare photograph of Nursing Matron Grace Eldrida Potter, the lone women in Canada’s Siberian Expeditionary Force, taken in Vladivostok, c. 1919. Potter sailed from Vancouver in November 1918 aboard the SS Monteagle, along with her husband, Col. Jacob Leslie Potter. She served with the Canadian Red Cross Mission in Siberia.

View more photos like this in the archive

The Canadians spent the winter and spring of 1919 “doing nothing” in Vladivostok, as one soldier wrote in his diary. Domestic unrest in Canada, combined with disunity among the Allies and the growing partisan insurgency, convinced Canada's government to bring the troops home — rather than deploy them “up country” into the Siberian interior (the original purpose of the mission).

The Canadians occupied themselves with routine drill at their barracks and recreational forays into Vladivostok. In the cosmopolitan port, soldiers from nearly a dozen Allied armies interacted with local civilians and refugees who had fled the interior — “the backwash of the revolution” in the words of a foreign visitor. The Canadians established two brigade newspapers, hiked on the seashore, forests, and ramparts surrounding the town, and kept active with a hockey league, soccer league, boxing matches, and a “gymkhana” sports day, organized on 1 May 1919 for the Allied contingents and local dignitaries.

Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection, 2005110-009 p23

Gymkhana sports day, Vladivostok, 1 May 1919. Organized by the Canadians for the Allied contingents and White Russian dignitaries, the event concluded with a Bolshevik assassination attempt on General Horvath's car.

View more photos like this in the archive

Rank-and-file troops also frequented cinemas, cafes, outdoor markets, and the brothels that dotted seamy “Kopek Hill” above the city. More than one quarter of all hospital cases among the Canadian soldiers in Vladivostok related to venereal disease.2

Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection, 19980027-012 #25

A sex trade worker at "Kopek Hill," Vladivostok, 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Bryant Family Collection, Nanton, Alberta

Sex trade workers and a Canadian soldier at "Kopek Hill," Vladivostok, 1919. This seamy side of Vladivostok, a feature of all theatres of war, contributed to more than one-quarter of all hospital cases among the Canadians in 1918-1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

"That was a tough place, Vladivostok," Capt. Eric Elkington recalled. "It was wintertime and there were always people getting killed or shot in the streets." As a medical officer with the 16th Field Albulance, Elkington saw first hand the hardship and suffering in the city.

He recalls treating soldiers who had "annihilated themselves in a house of ill-fame" and witnessed a bank robbery in progress. The culprit ran into the street and was shot in the head by a guard: “He was piled up with the rest of the bodies, which was bigger than this room of dead bodies, frozen stiff. They couldn’t bury them. Hundreds of dead bodies in this place.”3 Canadian troops found a morbid form of entertainment visiting “The Morgue,” a dilapidated shed on a hill with “dead people just lying on the floor.”4

The Canadians had arrived in Vladivostok as a typhoid epidemic hit the city, prompting Elmsley and the Canadian command to ban contact between the troops and civilians. The order forbade the soldiers from frequently cinemas and cafes and travelling aboard the tramway system.

Eric Elkington Collection, Ladysmith, British Columbia

Canadian hospital in Vladivostok, c. 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Human suffering in Vladivostok was concentred around the city's central railroad station. Thousands of refugees had converged on Vladivostok in 1918 and 1919, fleeing the revolution and civil war in the Russian interior and riding the Trans-Siberian Railroad to the end of the line: Vladivostok. Lacking adequate shelter and sustenance, they set up camp within the railway station and in boxcars that dotted the railway sidings in the city.

Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Archival Collection

Civilians and horses mingle in front of the Vladivostok central train station, c. 1919.

View more photos like this in the archive

Elkington described Vladivostok’s bullet-scarred railway station as a “foul place” that housed refugees “reeking with typhus.” He elaborated:

The Trans-Siberian railway station in Vladivostok was full of thousands of starving refugees. Literally starving. They had a little area on the floor and they all had fled from the Bolsheviks. Well, we did what we could. We took some supplies, what we could. I can always remember having a loaf of bread, and a woman came rushing up, and I gave it to her, and she had the most starving looking baby you ever saw in your life.

...There were an old general and his wife, living in this used railway carriage. And they were selling what things they’d managed to escape with their life, which was a tea and coffee service, all in gold. And they’d sell a cup, and then a plate. And I said to this old general, “What’s going to happen when you’ve sold all that?” “We will just die,” he said. “We will just die.”

I suppose that was the most tragic scene. I’ve seen a great many tragic scenes in various parts of the world, but that — Vladivostok — was the worst.5

The Canadians' experience in Vladivostok was two-sided. Lacking authorization to fight the Bolsheviks and partisan insurgents, the soldiers' memories were coloured with fond times spent in a unique and exciting corner of the world. They played sports, developed friendships with soldiers and civilians, and found entertainment in downtown "Vladi." But these 4,000 "Canadian tourists" were in a warzone, during one of the most painful moments in Vladivostok's history. They therefore experienced the human suffering of war and vices particular to foreign soldiers overseas.

Notes

- 1 Diary of Eric Elkington, n.d. (c. January 1919), p. 2, E.H.W. Elkington Family Collection (private collection), Ladysmith, BC.

- 2 Daily Routine Orders, 11 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), Library and Archives Canada, RG9.

- 3 Eric Elkington interview, 24 January 1986, University of Victoria Archives and Special Collections, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 170.

- 4 Holmes to Mother, n.d., as quoted in Edith M. Faulstich, “Mail from the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force,” Postal History Journal 12, 1 (January 1968), p. 22.

- 5 Elkington interview, June 1980, UVASC, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 169.

Go to

La vie à Vladivostok

La plupart des 4200 Canadiens n'ont jamais quittés Vladivostok, une ville portuaire qui, selon un agent de la Gendarmerie, était « environ 90 pour cent Bolchévik ». Sans autorisation pour procéder dans l'intérieur sibérien, les troupes canadiennes « n'ont rien fait ». Ils s'occupèrent avec leurs responsabilités de garde, des défilés de routine, des activités physiques — comme le hockey, le soccer, la boxe, et des randonnées sur le bord de la mer et des forêts — et d'autres loisirs tels que des spectacles vaudeville, des cours de langue russe, deux journaux de brigade, et des congés dans la cité avilissante qu'ils appelaient « Vladi ».

Collection Sidney Rodger, Beamsville, Ontario

Carte postale montrant la rue Svetlanskaya à Vladivostok, c. 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Les souvenirs et photographies de soldats comme Eric Elkington offrent un aperçu fécond de la vie sociale des troupes et de leurs relations avec la population de Vladivostok, y compris un grand nombre de résidents chinois et coréen et de réfugiés de l'intérieur sibérien. Les souvenirs des soldats révèlent aussi le côté sombre de l'intervention militaire — la violence, la souffrance humaine, et l'exploitation sexuelle.

PROFIL

Le Capitaine Eric Elkington et l'hiver de 1918-1919

« Vue du bateau, la ville de Vladivostok fut de toute bonté tôt le matin. La ville suivait les courbes du reflet de la demi-lune sur la baie et me semblait beaucoup plus longue que large. Derrière la ville et devant le soleil montant, les collines étaient couvertes d'une douce neige. Nous pouvons reconnaitre plusieurs bâtiments importants dont une église grecque avec un grand dôme d'or brillant ».[5]

C'est ainsi que le médecin militaire Capitaine Eric Elkington décrit l'arrivée des troupes canadiennes à bord du SS Protesilaus dans la Baie « Golden Horn » de Vladivostok le matin du 15 janvier 1919.

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, Collection Raymond Gibson, 1977-157, C-91765

Navire transportant des troupes canadiennes au quai d'Egerscheld, Vladivostok, 1919. Egersheld, à quelques kilomètres au sud du centre-ville et près de l'embouchure de la Baie « Golden Horn », fut le site d'arrimage principale. Il fut aussi le site d'artillerie et des hangars d'approvisionnement canadien.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Que ressemble-t-il aujourd'hui

Les premières troupes canadiennes atteignirent Vladivostok à la fin octobre 1918. Le commandant Major-Général James H. Elmsley installa son quartier général au majestueux Théâtre Pushkinsky — incitant les protestations d'hommes d'affaires de Vladivostok.

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des Archives George-Metcalf, 19980027-020 # 10

Théâtre Pushkinsky, quartier général des forces canadiennes du 27 octobre 1918 au 5 juin 1919. L'expulsion de la société d'Éclaircissement-culturel de Vladivostok, qui était propriétaire du bâtiment, suscita le ressentiment des hommes d'affaires de Vladivostok, qui organisèrent une grande manifestation. Malgré ce mécontentement, les Canadiens refusèrent de quitter les lieux.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Que ressemble-t-il aujourd'hui?

Pour préparer l'arrivée de la majorité des troupes canadiennes, les officiers d'Elmsley et hommes enrôlés organisèrent les Baraquements « Second River » et de la Baie Gornostai, et ouvrirent une école de formation d'officiers russes Blancs à l'embouchure de la Baie « Golden Horn » (Zolotoi Rog).

Cinq délégués commerciaux canadiens arrivèrent également à Vladivostok, et établirent un bureau de la Commission économique canadienne-siberienne sur la rue Svetlanskaya, avec l'objectif de renforcer les intérêts commerciaux du Canada en Sibérie et en Extrême-Orient russe. Ces aspirations n'aboutit à rien et reflète les conditions économiques chaotiques de la guerre civile. Mais la Banque Royale du Canada exploita néanmoins une succursale à Vladivostok pendant l'hiver 1918-19.

Collection Eric Elkington, Ladysmith, Colombie-Britannique

Baraquements canadiens à la Baie de Gornostai, à l'est de Vladivostok, 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Que ressemble-t-il aujourd'hui?

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, Collection Raymond Gibson, 1977-157, C-91757

Baraquements canadiens à Vtoraya Ryechka (« Second River »), au nord de Vladivostok, 1919. L'Escadron B de la RGCN-O fut ici cantonné, ainsi que les civils russes Blancs déplacées par la Révolution.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Que ressemble-t-il aujourd'hui?

Avec l'arrivées des navires SS Teesta et SS Protesilaus la population canadienne à Vladivostok atteignit environ 4000 hommes — et une femme, l'infirmière Grace Eldrida Potter.

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des archives George-Metcalf, 2005110-009 p3

Photographie rare de l'infirmière Grace Potter Eldrida, la seule femme de la Force Expéditionnaire Canadienne en Sibérie, prises à Vladivostok, c. 1919. Potter parta de Vancouver en novembre 1918 à bord du SS Monteagle, avec son mari, le Colonel Jacob Leslie Potter. Elle servit la mission de la Croix-Rouge canadienne en Sibérie.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Les Canadiens passèrent l'hiver et le printemps 1919 à « ne rien faire » à Vladivostok, comme un soldat écrit dans son journal. Les troubles domestiques au Canada, ajoutés à la désunion entre les Alliés et l'insurrection partisane croissante, convainquirent le gouvernement canadien de rappeler ses troupes — plutôt que de les déployer dans l'intérieur sibérien (comme fut l'objectif originale de la mission).

Les Canadiens s'occupèrent avec des exercices militaires et des randonnées plaisante dans Vladivostok. Dans ce port cosmopolite, les soldats de près d'une dizaine d'armées Alliées interagissaient avec la population civile locale et les réfugiés qui avaient fui l'intérieur russe — « les remous de la Révolution » comme les appela un visiteur étranger. Les Canadiens établirent deux journaux de brigade, marchèrent sur le bord de la mer, dans les forêts, et dans les remparts qui entouraient la ville. Aussi, ils s'amusaient avec une ligue de hockey, une ligue de soccer, des matchs de boxe, et une journée sportive « Gymkhana », organisée le 1er mai 1919 pour les contingents Alliés et les dignitaires locaux.

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des archives George-Metcalf, 2005110-009 p23

Journée sportive « Gymkhana », Vladivostok, le 1er mai 1919. Cet événement, organisé par les Canadiens pour les autres contingents Alliés et dignitaires russes Blancs, finira avec une tentative d'assassinat Bolchévik contre le Général Horvath.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Les hommes de troupes fréquentèrent aussi les cinémas, les cafés, les marchés en plein air, et les bordels qui parsemaient la sordide « Kopek Hill ». Plus d'un quart de tous les cas d'hospitalisation parmi les soldats canadiens à Vladivostok fut liées aux maladies vénériennes.2

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des archives George-Metcalf, 19980027-012 # 25

Une travailleuse du sexe à « Kopek Hill », Vladivostok, 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Collection de la famille Bryant, Nanton, en Alberta

Travailleuses du sexe et un soldat canadien à « Kopek Hill », Vladivostok, 1919. Ce côté sordide de Vladivostok, une caractéristique de tous les théâtres de guerre, contribua à plus d'un quart de tous les cas d'hospitalisations canadiennes en 1918-1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

« Ce fut un endroit difficile, Vladivostok », nota le capitaine Eric Elkington. « C'était l'hiver et les rues étaient toujours pleines de cadavres et de gens qui se fessaient tuer ». En tant que médecin de la 16e division d'Ambulance de campagne, Elkington ressenti les difficultés et les souffrances de la ville.

Il se rappelle d'avoir traité des soldats qui s'avoient « anéantis dans une maison de débauche » et fut témoin d'un cambriolage de banque. Le coupable se sauva dans la rue et fut tirer dans la tête par un garde: « il fut entassée dans un tas de cadavres, qui était plus grand que cette pièce et totalement gelé. Ils ne pouvaient pas les enterrer. Il y a eu des centaines de cadavres dans ce lieu ».3 Des soldats canadiens trouvèrent une forme morbide de divertissement quand ils visitèrent « La Morgue », un hangar délabré sur une colline pleins de « cadavres allongés sur le sol ».4

Les Canadiens arrivèrent à Vladivostok lorsqu'une épidémie de typhoïde frappa la ville, incitant Elmsley et le commandement canadien d'interdire tout contacts entre troupes et civils. Les soldats furent empêché par l'ordonnance de souvent fréquenter les cinémas et cafés et de voyager à bord du tramway.

Collection Eric Elkington, Ladysmith, Colombie-Britannique

Hôpital canadien à Vladivostok, c. 1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

La gare centrale de la ville fut la scène principales des souffrances humaines à Vladivostok. En 1918 et 1919, des milliers de réfugiés fuyant la Révolution et la guerre civile russe aboutirent à Vladivostok, le terminus du chemin de fer Transsibérien. Sans logement et nourriture, ils campèrent dans la gare et dans les wagons qui parsemaient les voies.

Musée canadien de la Guerre, Collection des archives George-Metcalf

Civils et Chevaux se mêlent devant la gare centrale de Vladivostok, c.1919.

Voir d'autres photos semblables dans l'archive

Elkington décrit la gare ferroviaire de Vladivostok comme criblée de balles, une « mauvaise place » qui logèrent des réfugiés « puant de typhus ». Il précisa:

« La gare Transsibérienne de Vladivostok tenait des milliers de réfugiés affamés. Véritablement affamés. Ils possédaient tous une petite place par terre et avaient tous fuis les Bolchéviks. Eh bien, nous avons fait ce que nous pouvions. Nous avons trouvés certaines provisions, tout ce nous pouvions. J'oublierai jamais d'avoir donné une miche de pain à une femme qui portait le bébé le plus affamé que j'ai jamais vu.

... Il y avait un vieux général et sa femme qui vivaient dans une vieille voiture de train. Ils vendaient tout ce qu'ils possédaient, et offraient un service de thé et café, tout en or. Et ils vendaient une tasse, puis une assiette. Et j'ai dit à ce vieux général, « Qu'est-ce qui va se passer lorsque vous aurez vendu tout cela »? « Nous allons simplement mourir », dit-il. « Nous allons simplement mourir ».

Je suppose que c'était la scène la plus tragique. J'ai vu beaucoup de scènes tragiques dans diverses parties du monde, mais Vladivostok - - fut la pire ».5

L'expérience des Canadiens à Vladivostok fut simultanément positive et négative. Manquant l'autorisation de combattre les Bolchéviks et insurgés partisans, les soldats se rappelèrent plutôt des bons temps qu'ils passèrent dans cette parti du monde unique et excitante. Ils jouèrent des sports, ils développèrent des amitiés avec d'autres soldats et civils, et trouvèrent une source de divertissement au centre-ville « Vladi ». Mais ces 4000 « touristes canadiens » se trouvaient dans une zone de guerre, au cours d'un des moments les plus douloureux de l'histoire de cette ville. Ils ressentirent ainsi la souffrance humaine et les vices de guerre qui caractérisent souvent l'expérience de soldats envoyés à l'étranger.

Notes

- 1 Journal d'Eric Elkington, s.d. (c. janvier 1919), p. 2, Collection de la famille E.H.W. Elkington (collection privée), Ladysmith, Colombie-Britannique.

- 2 « Daily Routine Orders », 11 décembre 1918, Journal de guerre du Quartier Générale de Guerre de la FECS, Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, RG9.

- 3 Interview avec Eric Elkington, le 24 janvier 1986, University of Victoria Archives and Special Collections, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 170.

- 4 Holmes à sa mère, s.d., cité dans Edith M. Faulstich, « Mail from the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force », Postal History Journal 12, 1 (janvier 1968), p. 22.

- 5 Interview avec Elkington, juin 1980, UVASC, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 169.

Sauter à

Жизнь во Владивостоке

Большая часть 4200 канадцев никогда не покидала Владивосток, портовый город, который один канадский офицер конной полиции окрестил городом, где «90% населения большевики». Из-за отсутствия указания двигаться вглубь страны, в Сибирь, канадские войска «ничего не делали»; они пытались сохранять занятость, несли вахту, участвовали в парадах, гнались за развлечениями: хоккеем, футболом и боксом, вечерними водевилями; издавали две газеты, брали уроки русского языка, гуляли по морскому побережью и лесу; совершали вылазки из бараков в город, который они называли Влади (Vladi).

Коллекция Сидни Роджера, г. Бимсвилль, Канада

Открытка городской жизни на ул. Светланская, г. Владивосток, 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Воспоминания и фотографии солдат, среди которых был Эрик Элкингтон, дают богатые представления о социальной жизни канадцев, об их взаимоотношениях с гражданским населением Владивостока, которое во многом состояло из большого числа этнических китайцев и корейцев, а также беженцев из Сибири. Воспоминания солдат также разоблачают темную сторону военной интервенции – насилие, человеческие страдания и проституцию.

Очерк

Капитан Эрик Элкингтон и Зима 1918-1919г.

«С борта нашего корабля, ранним утром, вид Владивостока был действительно очень красивым. Город тянется полумесяцем вдоль бухты, и, кажется, что он гораздо больше в длину, чем в ширину. За городом были слегка покрытые снегом холмы (сопки), над которыми солнце только начинало всходить. Мы могли хорошо различить лишь несколько строений, одним из которых была греческая церковь с большим золотым куполом, сияющим в первых лучах утреннего солнца.»[5]

Вот так военный врач Эрик Элкингтон описал приход канадского корабля «Протесилаус» во Владивостокскую бухту Золотой Рог утром 15 января 1919г.

Библиотека и Архивы Канады, коллекция Раймонда Гибсона, 1975-157, С-91765

Канадский корабль на вервях Эгершельда, Владивосток 1919г. В паре километров к югу от центра города, Эгершельд был главным месторасположением доков и верфей, где складировались канадские артиллерийские припасы и продовольственные грузы.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Как это выглядит сегодня

Первый отряд канадцев приплыл во Владивосток в конце октября 1918г. под командованием генерал-майора Джеймса Элмслея. Для нужд штаба ими был реквизирован грандиозный Пушкинский театр, что вызвало протесты Владивостокских торговых деятелей, которым принадлежал театр.

Канадский военный музей, коллекция Джорджа Меткалфа, 19980027-020 №10

Пушкинский театр, Канадский военный штаб с 27 октября 1918г. по 5 июня 1919г. Здание принадлежало Владивостокскому торгово-промышленному обществу, его реквизиция канадцами вызвала шквал протестов во Владивостоке, бизнесмены опубликовали открытую резолюцию протеста в местных газетах. Канадцы отказались освобождать театр.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Как это выглядит сейчас

Отряд Элмслея приступил к подготовке прибытия основных частей Канадских экспедиционных сил, организуя казармы на Второй речке (ныне район Зари) и в заливе Горностай, а также занялся открытием тренировочной школы для офицеров Белой армии на Русском острове.

Пять торговых комиссаров из Канады также прибыли во Владивосток, основав офис Канадско-сибирской экономической комиссиина ул. Светланская, которая искала способы укрепиться канадским коммерческим интересам в Сибири и на русском Дальнем Востоке. Эти стремления ни к чему не привели из-за беспорядочных экономических условий гражданской войны. Однако Канадский королевский банк достаточно быстро открыл свое отделение во Владивостоке зимой 1918-1919 г.

Библиотека и архив Канады, коллекция Раймонда Гибсона, 1977-157, С-91757

Канадские казармы на Второй речке (ныне Заря), северный Владивосток, 1919г., Там располагался полк Б канадских конных полицейских по соседству с гражданским населением («белые»), которых привела сюда революция из центра страны.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Как это выглядит сегодня

С прибытием кораблей «Тееста» и «Протесилаус» в январе 1919г. во Владивостоке насчитывалось более 4000 канадцев, среди которых была одна женщина - старшая медсестра Грейс Элрида Поттер.

Канадский военный музей, коллекция Джорджа Меткалфа 2005110-009 p3

Редкая фотография старшей медсестры Грейс Элриды Поттер, единственной женщины в рядах Канадских экспедиционных сил в России, фотография сделана во Владивостоке в 1919г. Поттер прибыла во Владивосток из Ванкувера со своим мужем полковником Джейкобом Лесли Поттером на корабле «Монтегл». Грейс Поттер работала в миссии Канадского Красного креста в Сибири.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Как писал один солдат в дневнике, всю зиму и весну 1919г. канадцы занимались «ничегонеделаньем» во Владивостоке. Внутренние беспокойства в Канаде вдобавок отсутствие единства среди союзников, плюс нарастающее партизанское движение привели канадское правительство к решению о возвращение войск домой, а не о дальнейшем продвижение сил внутрь страны, в Сибирь (как ранее планировалось).

Все свое время во Владивостоке канадцы занимали себя рутинной работой в казармах и развлекательными маршами во Владивосток. В космополитическом порте солдаты десятка союзнических стран вступали во взаимодействия с местными жителями и беженцами, что бежали из центральной части страны и стали, по словам иностранца, «отголосками революции». Канадцы основали две пехотные газеты, ходили по морскому берегу, гуляли по лесу, бродили по окрестностям города и проводили матчи хоккейной лиги, футбольные и боксерские соревнования, а также организовали состязание по перетягиванию каната, которое проводилось 1 мая 1919г. для союзнических сил и местных представителей.

Канадский военный музей, коллекция Джорджа Меткалфа, 2005110-009 р23

Перетягивание каната. Владивосток, 1 мая 1919г. Спортивное мероприятие, организованное канадцами, для союзнических сил и представителей белых властей, во время этого соревнования большевиками было предпринято неудачное покушение на генерала Хорвата в автомобиле.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Военные в звание часто встречались в кинотеатрах, кафе, городских рынках и публичных домах, что точечно располагались на «Сопке Копек» словно над городом. Более одной четверти всех обращений канадцев в госпитали было по причине венерических заболеваний.2

Канадский военный музей, коллекция Джорджа Меткалфа, 19980027-012 №25

Проститутка на сопке «Копек», Владивосток, 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Коллекция семье Браянт, г. Нантон, Канада

Проститутки и канадский солдат на сопке «Копек» во Владивостоке, 1919г. Одно из самых сомнительных мест Владивостока.

Больше фотографий в архиве

«Владивосток был жутким местом», - вспоминал капитан Эрик Элкингтон: «В то зимнее время на улицах города всегда кого-то убивали или в кого-то стреляли». Будучи военным врачом 16 полевого госпиталя, Элкингтон знал не понаслышке обо всех ужасах и страданиях в городе.

Элкингтон вспоминал также о лечение солдат, что «подвергали себя опасностям в домах дурной славы» и тех, кто был свидетелем ограбления банка. Грабитель выбежал на улицу и выстрелил в голову охранника: «мертвого свалили в замерзшею кучу тел в большой комнате, их даже невозможно было похоронить. Сотни тел в одном месте.»3 Канадские военные имели дурную привычку ходить в морг, ветхий сарай на сопке, как на развлечение.4

Канадцы прибыли в город, где свирепствовала эпидемия брюшного тифа, Элмслей и канадское командование запретило иметь контакты между войсками и гражданскими. Приказ запрещал солдатам посещать общедоступные кинотеатры и кафе, а также ездить в трамваях.

Коллекция Эрика эЭлкингтона, г. Лэдисмит, Канада

Канадский госпиталь во Владивостоке, 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Железнодорожный вокзал во Владивостоке был центром человеческих страданий в городе. Тысячи беженцев скопилось во Владивостоке в 1918 и 1919гг.; спасаясь бегством от революции и гражданской войны в центральной России, они садились на поезда до конечной станции транссибирской железной дороги – до Владивостока. Испытывая большую нехватку в месте для проживания и в питание, они разбили лагерь прямо в здание железнодорожного вокзала и в вагонах по всей линии железнодорожных путей города.

Канадский военный музей, коллекция Джорджа Меткалфа

Граждане города и лошади на фоне главного ж/д вокзала Владивостока, 1919г.

Больше фотографий в архиве

Элкингтон описал обстрелянный пулями железнодорожный вокзал города как «клоаку», наводненную беженцами «носителями тифа». Далее он уточнил:

Транссибирский железнодорожный вокзал Владивостока был полон тысяч умирающих от голода беженцев. Буквально умирающих от голода. У них был лишь маленький кусочек пола на вокзале, все они бежали от большевиков. Ох, мы сделали все, что могли. Мы добыли немного продовольствия для них, только то, что смогли. Я буду всегда помнить, как на буханку хлеба бросилась женщина. Я отдал ей хлеб, у нее был явно умирающий от голода ребенок, которого только можно было видеть в жизни.

… Там также был пожилой генерал со своей женой, они жили в железнодорожном вагоне. Они продавали все свои вещи, что удалось увести с собой, среди которых были чайные и кофейные сервизы в позолоте. Вначале они продали мне кружку, затем и блюдце. И я спросил этого пожилого генерала: «Что же будет, когда вы продадите всё это?». На что он сказал, - «Мы умрем». «Мы просто умрем».

Я думаю, это была самая трагическая сцена в моей жизни. Я видел огромное количество трагедий в разных частях мира, но во Владивостоке они были самые жуткие.5

Канадский опыт пребывания во Владивостоке имел две стороны. Не имя указания сражаться с большевиками и партизанами, воспоминания солдат были полны описанием времени, что они проводили в уникальном и захватывающем уголке мира. Они занимались спортом, дружились с солдатами и горожанами, находили развлечения в центре «Влади». Но все же эти 4000 «канадских туристов» пребывали на территории войны, в самый болезненный момент Владивостокской истории. Поэтому они испытали на себе людские страдания и специфические пороки не чуждые солдатам за рубежом.

Примечания

- 1 Diary of Eric Elkington, n.d. (c. January 1919), p. 2, E.H.W. Elkington Family Collection (private collection), Ladysmith, BC.

- 2 Daily Routine Orders, 11 December 1918, War Diary of Force Headquarters CEF(S), Library and Archives Canada, RG9.

- 3 Eric Elkington interview, 24 January 1986, University of Victoria Archives and Special Collections, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 170.

- 4 Holmes to Mother, n.d., as quoted in Edith M. Faulstich, “Mail from the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force,” Postal History Journal 12, 1 (January 1968), p. 22.

- 5 Elkington interview, June 1980, UVASC, Military Oral History Collection, SC 141, 169.

Перейти к

Special Exhibit

Exposition spéciale

Специальная выставка

Research Question

What was the experience of the 4,000 Canadians stationed in Vladivostok in 1919?

Key Themes

- • Day-to-day life of the soldiers, including recreational pursuits, sporting events, culture, and outings to downtown "Vladi" from the barracks at Second River and Gornostai Bay

- • Social conditions in Vladivostok, a city strained by dislocation of revolution and the influx of thousands of desperate refugees

- • Logistics of the Canadian and Allied occupation of Vladivostok, including the requisition of headquarters, barracks, docking, and ordnance facilities

Question de recherche

- Qu'expérience-t-il les 4000 Canadiens stationnés à Vladivostok en 1919?

Principaux thèmes

- • La vie quotidienne des soldats stationnés aux baraquements « Second River » et à la Baie de Gornostai, y compris des activités récréatives, sportives, culturelles, et des sorties au centre-ville « Vladi »

- • Les conditions sociales à Vladivostok, une ville poussé à ses limites par les bouleversements économiques causé par la révolution et de l'influx de milliers de réfugiés désespérés

- • Les installations de soutien logistique de l'occupation canadienne et Alliés de Vladivostok, y compris la réquisition de quartiers généraux, baraquements, quais, et munitions

Исследуемый вопрос

- Какой опыт получили 4000 канадцев во Владивостоке в 1919г.

Ключевые вопросы

- • Ежедневная жизнь солдат: погоня за развлечениями, спортивные турниры, культурные события и загородные прогулки от казарм Второй речки и Горностая до центра «Влади»

- • Социальные условия во Владивостоке из-за революционных событий и большого притока отчаявшихся беженцев

- • Канадская и союзническая оккупация Владивостока: реквизиция штабских помещений, казарм, доков и артиллерийского оборудования

Maps

- Map of key sites relating to Canada's occupation of Vladivostok

- Map of the City of Vladivostok, 1918

- Map of Golden Horn Bay, c. 1919 and surrounding City of Vladivostok

- Map of Vladivostok, drawn by a Canadian cartographer, with Pushkinsky Theatre in centre, c. 1919

- Map of Gornostai Barracks (1)

- Map of Gornostai Barracks (2)

Primary Documents

- Diary of Eric Elkington

- Protest resolution by Vladivostok Trade-Manufacturers' Assembly

- Response of Canadian command to businessmen's protest

- Diary of Charles Hertzberg (coming soon)

- Letters of Harold Steele (coming soon)

Multi-Media

- Eric Elkington interview on Vladivostok

- Video from Gornostai Bay Barracks

- CBC radio documentary on "Canada and the Siberian Intervention" (1970)

Photographs from the Digital Archive

- Gornostai Barracks

- Second River Barracks

- Droshky on Svetlanskaya Street

- Riding the tram into Vladivostok

- Korean fishers at Gornostai Bay

- Sex trade workers at "Kopek Hill"

- Vladivostok Railroad Station

- Bodies in "The Morgue"

Secondary Sources

Plans

- Plans des sites stratégiques liés à l'occupation canadienne de Vladivostok

- Plan de la ville de Vladivostok, 1918

- Plan de la Baie « Golden Horn », C. 1919 et autour de la ville de Vladivostok

- Plan de Vladivostok, établi par un cartographe du Canada, avec le Théatre Pushkinsky dans le centre, c. 1919

- Plan des Baraquements de Gornostai (1)

- Plan des Baraquements de Gornostai (2)

Documents primaire

- Journal de Elkington Eric

- Protestation de l'Assemblée du commerce et des fabricants de Vladivostok

- Réponse du commandement canadien à la protestation

- Journal de Charles Hertzberg

- Lettres d'Harold Steele

Multimédia

- Interview avec Eric Elkington au suject du Vladivostok

- Vidéo des Baraquements de la Baie de Gornostai

- Documentaire radio de la CBC sur « Canada and the Siberian Intervention » (1970)

Photographies de l'Archive numérique

- Baraquements Gornostai

- Baraquements « Second River »

- Droshky sur la rue Svetlanskaya

- Rouler sur le tram de Vladivostok

- Pêcheurs coréens à la Baie de Gornostai

- Travailleuse du sexe à « Kopek Hill »

- Gare de Vladivostok

- Cadavres dans « The Morgue »

Sources secondaires:

Карты

- Карта ключевых мест, реквизированных канадцами во Владивостоке

- Карта Владивостока, 1918г.

- Карта бухты Золотой Рог и окрестностей Владивостока, 1919г.

- Карта Владивостока, нарисованная канадским картографом, с Пушкинским театров в центре (здание канадского штаба)

- Карта казарм на Горностае (1)

- Карта казарм на Горностае (2)

Первичные документы

- Дневник Эрика Элкингтона

- Резолюция протеста Владивостокского торгово-промышленного общества

- Ответ Канадского командования на резолюцию протеста

- Дневник Чарльза Хертзберга

- Письма Харольда Штиля

Мультимедиа

- Интервью Эрика Элкингтона

- Видео: казармы на Горностае

- Радио CBC «Канада и интервенция в Сибири» 1970г.

Фотографии цифрового архива

- Казармы Горностая

- Казармы Второй речки

- Дрошки на Светланской улице

- Прогулка на трамвае по Владивостоку

- Корейские рыбаки в Горностае

- Проститутки на сопке «Копек»

- Владивостокский железнодорожный вокзал

- Тела в «морге»

English

English Français

Français Русский

Русский